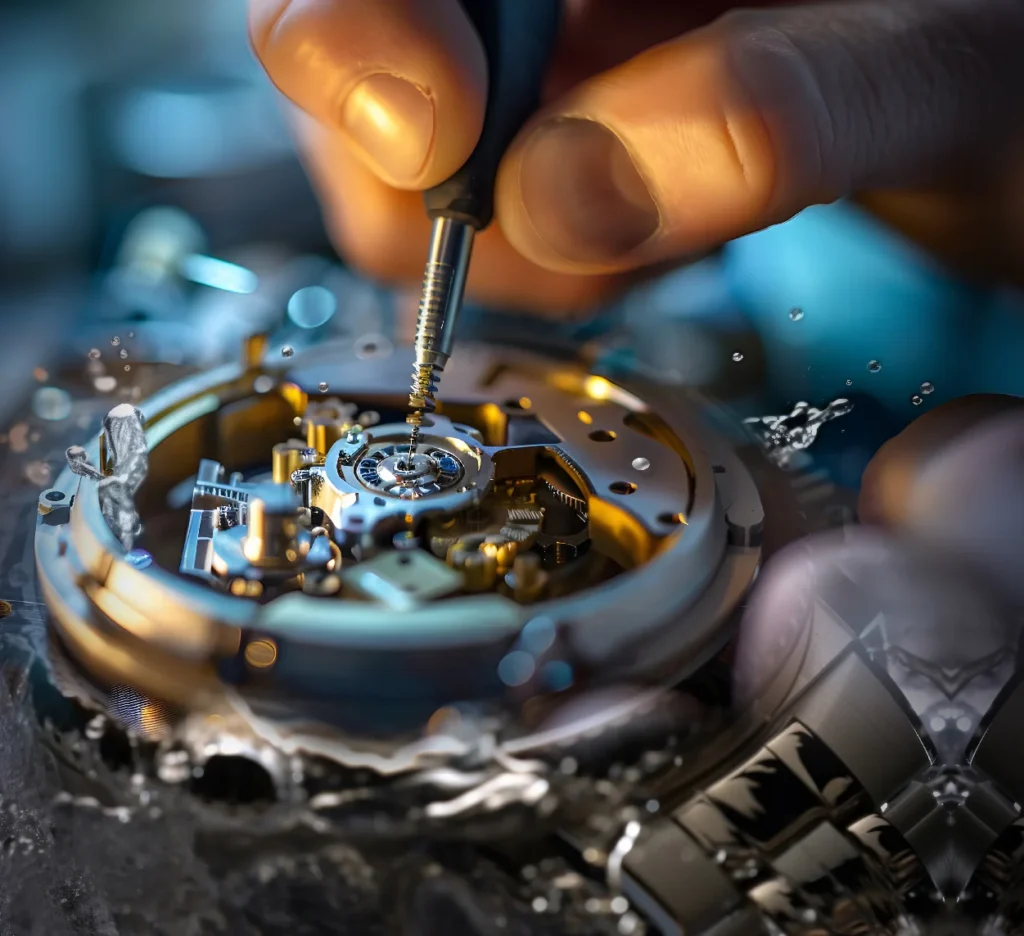

The first truth worth repeating is that no quick household trick replaces the work of a skilled watchmaker. Moisture intrusion is a serious fault, whether the watch in question is quartz, mechanical, hybrid, or solar-powered. The reason is simple: water is both a conductor and a corrosive agent. It creeps through tolerances measured in microns, oxidises alloys, stains dials, clouds lubricants, and in quartz movements, it can short-circuit the integrated circuit or battery terminals almost instantly. The advice that follows isn’t meant to substitute proper service — it’s intended to buy you precious time, to give the watch its best possible fighting chance before professional hands can open it up, dry it fully, and replace whatever gaskets or oils have already begun to fail.

So, what should you actually do?

The first step, without hesitation, is to remove the watch from your wrist. Human body heat is a silent accomplice in condensation — it increases the internal humidity and accelerates the migration of moisture into areas it might not have reached yet. Once it’s off, stay calm. The temptation to shake it, wave it, blow into it, or start pressing pushers and crowns must be resisted. Every movement of air, every tiny shock, risks spreading that moisture deeper into the calibre. You want to stop the problem from worsening, not distribute it evenly across the bridges and plates.

If your watch has a screw-down crown or pushers, leave them closed. Opening them risks inviting in more ambient moisture. However, if it has a simple friction-fit crown and you’re confident it’s externally dry, gently pulling it out to the neutral or setting position can sometimes create a small pressure equalisation route — a way for trapped vapour to find its way out. But this step should only be taken with absolute caution, ideally in a dry environment. Many people make the mistake of unscrewing the crown straight after removing the watch from a damp wrist, which can drag droplets straight into the tube.

Time, unfortunately, is the greatest enemy here. Corrosion starts within hours, particularly on untreated steel, brass, or the delicate hairspring of a mechanical movement. Your next goal, therefore, is to remove or neutralise as much internal moisture as possible before it oxidises anything important.

The most widely known remedy — the one almost every enthusiast mentions first — is uncooked white rice. It’s accessible, harmless, and passively absorbent. Place the watch, loosely wrapped in a clean microfibre cloth to avoid scratching, inside a sealable container filled with dry rice and leave it for at least 24 hours, ideally 48. The rice acts as a basic desiccant, drawing vapour from the microclimate around the watch. The effect isn’t rapid, but it’s steady. The physics behind it lies in hygroscopic absorption — starch granules in rice bind with water molecules in the air, gradually lowering the humidity in the sealed space. It’s not a miracle cure, but it’s certainly better than allowing the watch to sit exposed.

A more efficient alternative is silica gel — the same desiccant used to protect electronics and camera lenses from moisture. Silica gel can absorb up to 40 per cent of its own weight in water, far more than rice, and does so without breaking down or creating dust. If you’ve ever wondered why serious collectors keep sachets of these small white packets in their watch boxes, this is exactly why. Placing a fogged watch in an airtight container with silica gel packs is one of the best emergency interventions possible. Leave it untouched for a day or two, and resist the temptation to check progress too soon. It’s a slow extraction process, not a rescue you can rush.

If neither rice nor silica is available, gentle indirect heat can sometimes help. The emphasis here is on gentle. A desk lamp, radiator, or airing cupboard can provide a steady warmth of around 35–40°C — enough to promote evaporation without warping gaskets, damaging seals, or softening adhesives used in dial appliqués or rehaut markers. Never use a hairdryer or oven, as both deliver uneven heat that can cause crystal expansion or even shock fractures in sapphire. The goal is simply to nudge the internal air temperature up enough that the moisture evaporates and diffuses through existing micro gaps in the case sealing. This is where my decades of experience came in. I constantly think of ideas and came across the Travel Dry (Below). Its primary use is to dry the inside of boots, but it can also be used in a dry boot. On more than one occasion, I’ve put a moisture-laden watch in a dry boot, and the dryer does the same to the moisture in the watch as it would to the inners of a wet boot.

The Travel Dry DX works in a few simple steps. First, the dryer draws fresh air inside your shoes. Once inside, the heating elements warm the fresh air, helping it to circulate throughout the inside of your shoe. This warm air sucks up trapped moisture and escapes through the top of the shoe, taking the moisture with it. I’m betting there aren’t many people who’ve thought of applying this idea to watches. Its simplicity is pure genius.

Older watches, particularly those with acrylic crystals, sometimes respond well to a simple method: place the watch face down on a folded paper towel under a warm lamp. The mild heat and the capillary action of the towel can draw some vapour through the crystal interface — it’s one of those small folk techniques that, in certain circumstances, really can make a difference. Acrylic has slightly higher permeability than mineral or sapphire, meaning tiny amounts of water vapour can diffuse through it when warm. But again, patience and caution are everything.

here this becomes more complex — and more interesting from a technical standpoint — is in understanding why vapour forms in the first place. It isn’t always because the watch is flooded. Sometimes, it’s simply physics. A sealed case traps a finite volume of air. If that air contains humidity, and the temperature suddenly drops — say, when you step from a warm room into the cold outdoors — the dew point within that microclimate is reached, and condensation forms on the coolest internal surface: the underside of the crystal. It’s not necessarily that water entered from outside; it’s that moisture already inside the case condensed. This is common in watches with ageing gaskets or with crowns left unscrewed in humid environments.

Rubber gaskets, whether nitrile, silicone, or fluorocarbon (such as Viton), degrade over time. They compress, flatten, and lose elasticity. Some absorb trace moisture through microscopic fissures invisible to the eye. Even modern dive watches, with their elaborate sealing systems and multiple O-rings, are vulnerable if those gaskets have not been replaced at service intervals. In certain designs, the helium escape valve can even become a weak point if the spring mechanism or gasket seat is contaminated with salt. Every seal in a watch, from crystal gasket to crown tube, is only as reliable as the care given to it.

Professional watchmakers use vacuum testers or dry pressure testers to check case integrity. A simple low-pressure test can reveal micro leaks invisible under normal use. In a workshop environment, the proper procedure after detecting moisture involves opening the case, removing the movement entirely, drying both case and movement separately in a controlled low-humidity chamber, cleaning corrosion-prone areas, and re-lubricating all seals before reassembly. Some use specialised equipment such as Elma vacuum dryers or Bergeon heat chambers designed to safely pull moisture out without overheating the oils.

For quartz watches, the process becomes even more delicate. Water or condensation can short the circuit board or corrode the coil wire. In many instances, the damage might not show immediately — the watch might even resume ticking — but internal oxidation will continue to eat away at contacts and traces until one day the module dies unexpectedly. In that sense, vapour intrusion is like rust beneath paint: unseen, slow, and irreversible unless properly removed early.

A mechanical watch, meanwhile, has its own vulnerabilities. Steel pinions, untreated screws, and fine pivots can all begin to rust within hours. The setting lever spring, calendar jumper, or keyless works are often the first victims because they sit close to the case edge, where moisture gathers first. Even a small patch of oxidation can later break off and contaminate the gear-train, grinding itself through wheels or clogging the escapement. Lubricants emulsify under humidity, turning from clear synthetic oil into a cloudy paste that can seize pivots or create variable friction. All of this can occur long after the visible fog has vanished.

The tragedy is that many owners mistake a cleared crystal for a cured problem. Just because the fog fades doesn’t mean the watch is dry. It simply means the moisture has relocated — often beneath the dial, behind the date disc, or into the balance jewel. That’s why the most responsible next step, once you’ve stabilised the situation, is to take the watch to a professional as soon as possible. A skilled technician will open it, remove the dial and hands, clean the plates, dry the jewels under controlled heat, and replace the case gaskets. In extreme cases, movement parts are replaced, dials reprinted, and lume compounds reapplied. It’s not cheap, but neither is replacing an entire movement years later.

It’s easy to underestimate the emotional weight of this scenario. The moment you notice condensation under a crystal isn’t just a technical problem — it’s a psychological jolt. There’s panic, guilt, and that hollow feeling of seeing something precious in distress. In watch communities, I’ve read countless stories from owners describing the instant their heart sank — a diver after a swim, a vintage dress watch caught in rain, a chronograph worn during a humid run. The sense of helplessness is universal. Because we don’t just see fog; we see a fracture in our trust with the watch, that silent bond between human and machine, suddenly tested.

And yet, treating that fog correctly — calmly, knowledgeably, without resorting to reckless “hacks” — often saves the watch. Dry it safely, avoid aggressive heat, and act with methodical patience. Then, entrust it to the professionals. The peace of mind alone is worth it. Once restored, that same watch often returns with a new layer of meaning — it has survived something, endured an ordeal, much like its owner. And from then on, every glance at the dial carries a faint reminder of resilience.

If there’s one lesson, it’s that watches, like people, have limits. They endure pressure, temperature shifts, and environmental challenges. But neglect the small signs — that thin fog line beneath the crystal, that brief mist that “goes away” — and you invite a slow decay that no emergency trick can reverse. Whether it’s a humble Seiko or a cherished IWC, the principle is the same: when moisture intrudes, act quickly, think clearly, and respect the mechanical life beating inside. Because if the watch survives, it’ll not only tell the time — it’ll tell the story of how you both refused to surrender to it.

For Those Interested in the Science Behind the Fog

Every watch has its own internal weather system — a microclimate trapped behind the crystal. Understanding what causes vapour to appear, and how materials respond to it, adds a fascinating layer of insight into what’s really happening when fog forms. The science isn’t complicated, but it’s quietly beautiful once you know where to look.

When we talk about vapour intrusion, we’re really talking about physics and chemistry playing out inside a sealed environment that isn’t quite as sealed as we imagine. Every wristwatch, regardless of its water resistance rating, is a microclimate. Within its case, the trapped air contains moisture in the form of water vapour, even when perfectly dry to the touch. That moisture only becomes visible when the temperature and pressure conditions reach what’s called the dew point — the threshold at which water vapour condenses into liquid droplets.

Imagine walking from a warm living room into a cold winter evening. The sudden temperature drop cools the crystal of the watch faster than the air inside the case. That internal air, unable to hold the same level of moisture, releases some of it as condensation onto the coldest surface — the underside of the crystal. This is why fogging is often seen immediately after stepping outdoors or after a shower, not while you’re still in the warm environment. It’s a case of basic thermodynamics: warm, humid air meets a cold surface and sheds water.

The severity depends not only on the temperature difference but also on the permeability and composition of the watch’s materials. Acrylic crystals, for instance, are more porous than mineral glass or sapphire. That’s why older watches with domed acrylic lenses often “breathe” — allowing minuscule exchanges of air and moisture over time. Sapphire, by contrast, is extremely non-porous but rigid, which means any seal failure elsewhere (like the crown tube or caseback gasket) becomes more critical, since the crystal itself won’t release any vapour naturally. Some modern dive watches mitigate this with inert-gas filling, replacing internal air with nitrogen or argon to lower humidity and prevent condensation altogether. It’s the same principle used in camera lenses and high-end optics.

Then there are the gaskets — the unsung heroes of water resistance. They come in several materials, each with its advantages and weaknesses. Nitrile rubber (NBR) is common in affordable watches; it’s oil-resistant and inexpensive but degrades over time under UV and ozone exposure. Silicone gaskets remain flexible for years and perform well across temperature extremes, but they can compress and “take a set”, losing their elasticity after repeated tightening of the caseback or crown. Fluorocarbon gaskets, like Viton, are chemically superior — resistant to heat, solvents, and ageing — which is why they’re preferred in higher-end tool watches and dive models. Over time, though, even Viton loses volume, particularly if the watch hasn’t been serviced and the gasket sits under continuous compression.

What’s less widely known is that water resistance isn’t static — it’s a decaying property. A brand-new 200-metre-rated diver may easily pass pressure tests when fresh from the factory, but after two or three years of wear, microscopic changes in gasket geometry can cut that margin by half or more. The oils used on seals (often silicone grease or fluorinated lubricants) also evaporate or migrate, leading to uneven sealing pressure. Combine that with thermal cycling — wrist warmth by day, cooler air at night — and you have constant expansion and contraction subtly working the seals loose. It’s why a properly serviced watch always includes gasket replacement, even if no visible leaks have ever occurred.

Professional watchmakers rely on pressure and vacuum testing machines to verify case integrity. These devices simulate atmospheric changes that would reveal leaks too small to see. A dry pressure tester works by placing the watch in a sealed chamber, increasing the pressure, and then measuring the case’s minute expansion. When the pressure is released, a sensor detects whether the case volume returns to normal instantly or lags slightly — the latter indicating trapped air escaping through a leak. Vacuum testers, by contrast, lower the pressure, observing whether the case expands abnormally as air seeps out. A watch that passes both tests can be considered well sealed, but only at that moment in time.

There’s also a subtle but important concept known as pressure differential fatigue. Each time you expose a watch to rapid pressure or temperature change — such as swimming in cold water after sunbathing, or entering an aircraft cabin from ground level — the case experiences micro-strain. Even sapphire crystals and stainless-steel cases flex by microns, but enough to affect gasket compression and seating. Over the years, this stress can create micro gaps invisible even under magnification, providing just enough room for vapour molecules to creep in. Once that happens, the damage is done — vapour intrusion is rarely a single dramatic event but the cumulative result of environmental fatigue.

From a watchmaker’s perspective, the aftermath of moisture ingress reveals itself through tell-tale signatures. Rust halos around screw heads, cloudy deposits under jewels, or slight green verdigris on brass components all signal electrochemical reactions triggered by water and oxygen. In some cases, the damage can be mapped like a forensic report — corroded keyless works indicate crown-tube failure, while moisture marks on the rotor bridge often point to caseback gasket failure or condensation drawn upward by temperature gradients. Quartz modules often show white crystalline corrosion on the battery contacts, a classic sign of capillary ingress through the case seam.

For the chemically curious, galvanic corrosion also plays a role. When dissimilar metals such as steel and brass are in contact and moisture bridges them, an electrochemical cell forms, causing the less noble metal (usually brass) to corrode faster. In hybrid constructions — like stainless cases with brass movement plates — this effect can accelerate dramatically. It’s one reason certain vintage movements, especially those using mixed alloys, suffer irreversible damage even after short exposure. Modern movements mitigate this through protective coatings and nickel plating, but nothing resists electrolysis indefinitely.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that moisture affects luminous compounds. Old tritium-based lume can react with water vapour, turning dark or flaky, while modern Super-LumiNova — though more chemically stable — can still stain or lose adhesion if the binder absorbs moisture. Dials with lacquered finishes can blister subtly, and printing inks may bleed microscopically along the grain of the surface. Even adhesive gaskets under sapphire crystals, especially in modular cases, can swell slightly, compromising alignment or tension.

All of this might sound daunting, but it ultimately reinforces one thing: vapour is not an accident; it’s a signal. A watch showing internal condensation isn’t crying for help — it’s whispering that something has already gone wrong in its equilibrium. The air inside that case, the gaskets sealing it, the materials forming its shell — all are part of a delicate system designed to resist intrusion. Once that balance is disturbed, only deliberate, informed care can restore it.

So next time you see fog beneath a crystal, remember that it’s not simply trapped humidity — it’s thermodynamics in miniature, chemistry in motion, and a reminder that even precision instruments breathe, age, and respond to their environment just as we do. And just as we’d see a doctor when something feels off, the watch deserves the same respect. A good watchmaker is, after all, both a surgeon and a scientist, restoring equilibrium to a mechanism designed to measure it.

Just About Watches

Just About Watches