Think of a watch as a perfectly choreographed ballet. Every wheel, lever, and spring performs in synchrony, keeping a rhythm so exact it can divide a single second into eight delicate beats. Now picture an invisible hand wandering onto that stage, pulling one dancer’s arm, freezing another mid-step, and spinning a third out of tempo. The choreography collapses — not from error, but interference. That’s magnetism inside a watch: an uninvited conductor, waving an unseen baton that ruins the score without touching a note.

To grasp why it’s so destructive, it helps to understand where it strikes. At the heart of every mechanical watch lies the balance spring — often called the hairspring — a coiled sliver of metal thinner than a human hair, controlling the oscillations of the balance wheel. It’s the watch’s pulse, expanding and contracting thousands of times per hour. If that spring becomes magnetised, even faintly, its coils can cling together, shortening their breathing space and throwing the watch’s timing into chaos. The result is usually dramatic — a watch that suddenly gains several minutes a day, seemingly possessed. Other steel components, such as pivots, levers, and screws, can also become magnetised, but the hairspring is the easiest target.

The irony is that when wristwatches first emerged in the early twentieth century, magnetism wasn’t seen as much of a threat. The world simply wasn’t as saturated in electromagnetic fields as it is today. There were tram lines, telegraph wires, and generators, but few people lived surrounded by laptops, smartphones, induction hobs, Bluetooth speakers, and the sea of magnets hidden in everything from handbags to headphones. A century ago, the average wristwatch faced far fewer invisible hazards. As the modern world became electrified, so too did the ambient magnetic landscape, and suddenly the mechanical watch — that exquisite miniature of human craftsmanship — found itself surrounded by unseen traps.

Watchmakers, of course, noticed. Accuracy was the one thing they could not compromise. As early as the nineteenth century, Vacheron Constantin was experimenting with antimagnetic properties, producing in 1915 one of the first watches resistant to magnetic influence by crafting a balance spring from palladium — a non-ferrous metal unaffected by magnetic fields. Two decades later, in 1930, Tissot unveiled the Antimagnetique, widely recognised as the first truly antimagnetic wristwatch. Its secret lay in using new alloys for the escapement and balance spring, reducing their attraction to magnetic flux. These early advances were less about fancy marketing and more about survival; industrialisation had created a new enemy, and watchmakers were determined to fight back.

By the mid-twentieth century, however, a new strategy emerged — not altering the vulnerable parts, but protecting them outright. This was the age of shielding, and the idea came straight from physics. In 1836, the British scientist Michael Faraday discovered that a conductive enclosure could block external electric and magnetic fields. His discovery became known as the Faraday cage, and it wasn’t long before watchmakers realised that this principle could be adapted to defend their creations. By encasing the movement in a soft iron inner shell, they could divert magnetic flux around it, keeping the heart of the watch safe.

The beauty of this solution lay in its simplicity: magnetism would always take the path of least resistance. The soft iron cage acted as that path, drawing magnetic lines of force away from the delicate balance spring like a lightning rod channelling energy harmlessly into the ground. Rolex, IWC, and Omega all seized on this concept during the post-war period, when scientists, engineers, and technicians worked in environments filled with magnetic hazards.

Rolex’s Milgauss, released in 1956, became a legend of this era. It was designed specifically for engineers at CERN — the European Organisation for Nuclear Research — where magnetic fields could reach levels far beyond what ordinary watches could survive. The name itself came from “mille,” meaning a thousand, and “gauss,” a unit of magnetic density. In laboratory terms, a thousand gauss was an enormous threshold, yet the Milgauss met it with stoic reliability. Omega’s Railmaster, created the same year, targeted railway workers whose proximity to electrified rails posed similar threats. IWC joined the fray with the Ingenieur, a robust watch built to withstand the invisible fields that could otherwise render a chronometer useless. These were not fashion statements; they were functional instruments designed for people whose livelihoods depended on accuracy.

What’s often forgotten is that magnetism’s threat didn’t stop with those professions. The rise of household electrics and the spread of small personal electronics meant that even ordinary wearers faced exposure. So while scientists might have inspired the first antimagnetic watches, everyday life eventually demanded that the same technology become mainstream. This, in turn, spurred innovation in materials science — arguably one of the most transformative chapters in horology.

The first great leap came with alloys such as Elinvar and Nivarox, both engineered to resist temperature fluctuations and, crucially, magnetic interference. Nivarox, an acronym derived from nicht variabel oxydfest (“non-variable, non-oxidising”), became the industry standard for hairsprings from the 1930s onwards. These alloys used combinations of nickel, chromium, and beryllium, producing a metal that was both elastic and resistant to magnetism. The development of such materials marked a quiet revolution: it meant that even standard wristwatches could survive moderate exposure to magnetic fields without spiralling out of accuracy.

Still, the ultimate solution was yet to come. Fast-forward to the twenty-first century and the emergence of silicon — a material that is, by its very nature, non-magnetic. In watchmaking terms, silicon was nothing short of a revelation. It doesn’t corrode, it’s lightweight, and it can be manufactured with extreme precision through photolithography — a process borrowed from the semiconductor industry. Patek Philippe, Ulysse Nardin, Omega, and Breguet were among the pioneers who saw its potential. A silicon balance spring doesn’t just resist magnetism; it’s immune to it. No Faraday cage required. No soft iron caseback. The dancer, to borrow the earlier metaphor, learns to ignore the invisible hand altogether.

But even silicon isn’t the end of the story. Magnetism, after all, is everywhere. We live inside a vast electromagnetic web — from Wi-Fi routers to electric cars, power cables, and smart devices, each one a small field generator in its own right. A single magnetic phone clasp or a car speaker magnet can throw a mechanical watch off balance. The fields may be faint, but the hairspring’s tolerance is microscopic. In daily life, that means it’s surprisingly easy to magnetise a watch without even noticing.

Modern watchmakers have taken creative steps to counter this. Omega’s Master Chronometer certification, for example, demands resistance to fields up to 15,000 gauss — fifteen times stronger than what the Milgauss could endure in the 1950s. They achieved this not through shielding, but through entirely non-ferrous components — silicon springs, titanium balance wheels, and proprietary alloys that render magnetism irrelevant. It’s a scientific marvel wrapped in stainless steel, a silent duel with invisible forces that most owners never even notice is happening.

It’s worth pausing on that figure — 15,000 gauss — because it’s enormous. To put it in perspective, an ordinary fridge magnet is about 50 gauss. A medical MRI scanner can exceed 70,000 gauss. So when a modern watch shrugs off 15,000 gauss as if it were a gentle breeze, it’s not a marketing gimmick. It’s an engineering statement: the kind that bridges centuries of physics, metallurgy, and miniaturisation.

And yet, the issue remains relevant precisely because magnetism is both invisible and cumulative. A watch might not suffer immediate chaos from one encounter, but repeated exposure can gradually alter its parts’ magnetic alignment. It’s why demagnetisers (degaussers) — those humble little devices often shaped like blue plastic squares — remain essential tools on any watchmaker’s bench. Inside is a coil that generates an alternating magnetic field. When a magnetised watch is exposed to it, the alternating polarity neutralises residual magnetism, restoring balance to the movement. It’s simple, quick, and almost magical to watch in action — a quiet hum and a click, and the watch returns to normal, as if exorcised of an unseen spirit.

The concept isn’t new; watchmakers have used demagnetisers since the early twentieth century, when electricity first became widespread. But their accessibility today has made them an invaluable household tool for collectors and enthusiasts alike. A watch running minutes fast after a trip through airport security or a few weeks resting near a laptop can often be restored in seconds with a demagnetiser. The simplicity of the solution belies the complexity of the science behind it.

For the curious, it’s also fascinating to consider how watch regulation interacts with magnetism. A mechanical movement is essentially a balance of competing forces: gravity, friction, inertia, and elasticity. Magnetism introduces a wild card by altering the magnetic permeability of steel parts — in essence, changing how easily they become magnetised and how they retain that charge. The effects can be subtle, but they compound rapidly. A hairspring that clings together on just one coil throws off the isochronism of the entire system, causing the balance to oscillate faster than it should. In a world measured in fractions of seconds per day, that’s enough to send accuracy into disarray.All of which makes the ongoing arms race against magnetism rather poetic. Watchmaking has always been an act of defiance against nature — conquering gravity through tourbillons, temperature through alloys, pressure through case design, and now magnetism through both material and mind. Every step forward in horology has been a dialogue with invisible forces. Magnetism, perhaps more than any other, captures that tension between the physical and the unseen. It’s a force that doesn’t break the watch — it merely whispers chaos into its rhythm, and the watchmaker’s task is to restore order.

Looking ahead, the story is still unfolding. With electric vehicles, wireless charging, and wearable tech on the rise, the magnetic fields of our world will only grow stronger. Already, some brands are exploring graphene and other carbon-based composites that promise the same non-magnetic resilience as silicon but with greater shock resistance. Others are integrating hybrid shielding systems that combine traditional Faraday cages with modern materials. Even the humble caseback design — often overlooked — plays a role, with certain geometries better suited to redirecting flux lines than others.

It’s tempting to imagine a future where magnetism ceases to matter, where every watch is immune by design. But perhaps that would take some of the romance out of it. The very fact that magnetism still poses a challenge keeps horology alive as both art and science. The invisible force that once plagued early chronometers now fuels an entire field of research and invention — one that blends metallurgy, physics, and creativity in equal measure.

And this is where the story deepens — into the laboratories and patent offices where the war against magnetism truly played out. The alloys and materials we now take for granted were born not of sudden genius, but of decades of incremental experiments. In Switzerland’s Vallée de Joux, engineers were quietly filing patents for temperature- and magnetism-resistant hairsprings as early as the 1920s. The Compagnie des Métaux Précieux developed Elinvar (short for “elastic invariable”) in 1919, its key property being a near-zero change in elasticity across temperatures. But by happy coincidence, Elinvar was also far less magnetic than traditional steel, setting the stage for Nivarox, Parachrom, and every silicon derivative that followed.

Nivarox SA, founded in the 1930s and later absorbed into the Swatch Group, became the unseen powerhouse of precision timekeeping. Almost every Swiss brand, from Longines to Omega, relied on its balance springs, all drawn from a single metallurgical formula perfected through experimentation with nickel-iron-chromium alloys. The exact proportions were fiercely guarded secrets. In effect, Nivarox became the invisible spine of Swiss horology — a quiet monopoly on the rhythm of mechanical time.

Then came Parachrom, Rolex’s answer to magnetism and shock. Introduced in the early 2000s, Parachrom Bleu combined niobium and zirconium in an oxide-treated alloy that resisted both corrosion and magnetic fields. Its distinct blue hue wasn’t just aesthetic; it was the surface oxide layer that further stabilised the metal’s properties. Few realise that Parachrom isn’t fully non-magnetic — it’s highly resistant — but that nuance underscores Rolex’s pragmatic approach: it didn’t seek to reinvent the physics, only to control it.

Meanwhile, Omega and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) pursued an entirely different frontier — silicon. The resulting Si14 hairspring, unveiled in 2008, became the foundation for the brand’s Master Chronometer certification. Silicon’s crystalline structure meant perfect consistency, but it also introduced challenges of its own: brittleness, cost, and a lack of easy adjustability. Where a steel spring could be bent, shaped, or re-regulated by hand, a silicon one had to be engineered to perfection from the start. It forced a new kind of precision: design-based, not hand-based.

Patents from this era read like the diary of a scientific arms race. Ulysse Nardin’s Freak of 2001 used silicon escapement wheels and anchors, reducing both friction and magnetic susceptibility. Patek Philippe’s Spiromax hairspring followed in 2006, featuring a patented terminal curve that mimicked Breguet’s traditional overcoil but in monocrystalline silicon. Breguet’s Magnetic Pivot system flipped the problem entirely, using magnetic repulsion to suspend the balance staff between opposing magnets — turning the enemy into an ally. It was one of the most elegant inversions of the problem ever achieved, the equivalent of training the invisible hand to dance with the watch instead of against it.

If the twentieth century’s challenge was shielding, the twenty-first century’s is adaptation. Magnetism has evolved from a problem of external interference to a property to be harnessed. The same fields that once ruined accuracy are now being studied for micro-levitation, friction reduction, and shock absorption. Materials once considered too exotic — amorphous metals, carbon nanocomposites, graphene sheets — are slowly finding their way into escapements and gear trains. Their properties are as poetic as they are practical: hardness without brittleness, elasticity without magnetism, and mass without density.

Some of these experiments have already yielded results. TAG Heuer’s Isograph hairspring, announced in 2019, used a carbon composite derived from nanographene, boasting near-perfect resistance to magnetism and temperature. Although early production issues halted the line temporarily, it proved one thing beyond doubt — the race for the perfect non-magnetic oscillator isn’t over. It’s simply moved from the workbench to the lab.

It’s also telling that certification standards have had to evolve alongside these materials. The Swiss Official Chronometer Testing Institute (COSC) historically tested for accuracy in various positions and temperatures but ignored magnetism. Omega’s Master Chronometer and METAS standards changed that, introducing rigorous magnetic exposure tests up to 15,000 gauss as part of official certification. This wasn’t just a new benchmark; it was a public statement that the industry had crossed a threshold.

And yet, as the science surges forward, the essence remains the same. Whether the spring is palladium, Nivarox, silicon, or graphene, it’s still performing the same ancient task — expanding and contracting to mark time’s rhythm. Every technological leap, from Faraday cages to nanomaterials, serves that same purpose: keeping the beat pure.

Perhaps that’s the quiet magic of magnetism in horology. It has forced the industry to become more than artisans of steel and jewels; it has turned watchmakers into physicists, metallurgists, and inventors. The struggle against the unseen has always defined human ingenuity, and nowhere is that truer than on the wrist. The invisible force still surrounds us, humming through circuits and cables, whispering through satellites and screens. But so too does the response — the ticking defiance of a machine that refuses to yield to invisible interference. It’s there in every balance wheel, every oscillation, every measured beat against the chaos of modern life.

The story of magnetism in watchmaking isn’t finished; it’s evolving in real time. Each new alloy, each lab-grown material, and each quietly filed patent represents another verse in an ongoing dialogue between human precision and the universe’s invisible hand. And that, perhaps, is what makes horology so endlessly fascinating — it’s not just the measurement of time, but the mastery of everything that tries to distort it.

And that’s the thing about magnetism — it’s not just a scientific problem, it’s a story. Somewhere along the line, that invisible enemy became a marketing ally. The moment watchmakers realised people feared what they couldn’t see, they also realised they could sell them the reassurance that came from conquering it. Antimagnetic didn’t just mean protection; it meant progress. It was the watchmaker’s way of saying: we’ve mastered something nature itself hides from your senses. By the middle of the 20th century, that word began to carry almost mythical weight. It appeared on dials like a badge of modernity, often in the same confident script that once declared “Waterproof” or “Shockproof.” In a time when technology was both exciting and intimidating, the notion that your watch could defy invisible forces was quietly reassuring. You weren’t just wearing a timepiece — you were wearing a tiny declaration of scientific control in a world becoming increasingly complex.

There was a cultural context, too. The 1950s and 60s weren’t just about wristwatches; they were about mankind’s growing fascination with science itself. Nuclear power, aviation, radar, and early computing were transforming everything from transport to the kitchen. Science was no longer confined to laboratories — it had entered everyday life. And yet, it was still mysterious, filled with words like “radiation,” “magnetism,” and “electrons,” that felt equal parts wonder and worry. Watchmakers understood that tension and learned how to position themselves within it. They began producing not only anti-magnetic watches, but stories — stories that painted the watch as a trusted companion in a world of unpredictable forces.

Rolex’s Milgauss, Omega’s Railmaster, and IWC’s Ingenieur weren’t just mechanical achievements; they were cultural products of that atomic age optimism. Even the names sounded like characters in a science fiction novel. The Milgauss wasn’t just another Rolex — it was a “scientist’s watch,” advertised with imagery of laboratories, Tesla coils, and men in white coats. Omega’s Railmaster echoed the romance of modernity, built for men who tamed the new iron arteries of industry. IWC’s Ingenieur, with its distinctive lightning-bolt seconds hand, became a visual metaphor for harnessing energy itself. These watches didn’t simply protect against magnetic fields; they reassured their owners that human ingenuity could triumph over the invisible.

It’s worth pausing to appreciate how subtle this psychological shift was. Antimagnetism became one of those rare horological innovations that bridged technical merit and emotional resonance. It wasn’t like a tourbillon, which dazzled collectors but was largely irrelevant to most wearers; antimagneticism spoke to something universal — the desire for reliability in a world of unseen chaos. People didn’t need to understand how a Faraday cage worked to feel better knowing it was there. In that sense, the anti-magnetic watch became an early exercise in invisible luxury: value you couldn’t see, but could feel in the confidence it gave you.

By the 1970s, as industries electrified and the quartz revolution loomed, magnetism was no longer an exotic threat faced only by engineers and railwaymen. Everyday consumers were surrounded by new appliances, televisions, tape decks, and the growing hum of electromagnetic interference. The public’s understanding of magnetism was limited, but their awareness was rising, and brands were quick to adapt. Japanese manufacturers like Citizen and Seiko began incorporating anti-magnetic standards into mass-market models, marking them discreetly on casebacks or movement plates. It wasn’t a feature to boast about anymore — it was becoming an expectation. Much like waterproofing, antimagnetism was evolving from a specialist strength into a baseline of quality.

Yet even as silicon and advanced alloys made magnetic immunity almost trivial for high-end brands, the emotional power of that word — “antimagnetic” — persisted. It taps into something fundamental: the reassurance that your watch can endure what you cannot perceive. In an odd way, that has only grown more relevant in the digital age. We might not fear magnetic fields like our grandparents did, but we live surrounded by invisible data waves, signals, and frequencies that define modern life. The old paranoia has simply changed shape. A truly great watch still plays into that old psychological need — the comfort of mechanical certainty in an uncertain, intangible world. When you think about it, magnetism gave horology one of its greatest metaphors. Every watchmaker, from the smallest atelier to the biggest luxury house, has to contend with unseen forces — whether it’s gravity, shock, or time itself. Magnetism became a symbol of mastering the unseen. And as materials improved, that mastery became almost poetic. Consider the leap from the first palladium hairspring to today’s silicon marvels. What began as metallurgy evolved into microengineering, merging traditional craft with nanoscopic precision. It’s one of the few places where horology genuinely overlaps with aerospace and semiconductor science. The same cleanroom technology used to etch microchips now produces balance springs so thin and flawless that they might as well be invisible.

Still, no matter how perfect the technology becomes, the human relationship with magnetism remains oddly superstitious. Ask a collector about magnetised watches and you’ll still hear half-myths and old wives’ tales — everything from running it past a speaker magnet to sticking it in the fridge (please don’t). It’s fascinating how something so quantifiable still invites folklore. That might be because, in the mind of the enthusiast, magnetism isn’t just a field — it’s a story about control and chaos. When a watch suddenly gains minutes a day, it feels possessed. When a simple demagnetiser restores it to health, it feels like an exorcism. And in a way, that’s what watchmaking has always been about: exorcising chaos.

This blend of science and superstition makes magnetism one of the most human aspects of horology. It’s invisible, it’s powerful, and it reminds us that even our most precise creations exist at the mercy of nature’s whims. It humbles both maker and wearer. The fact that a spring thinner than a hair can still be influenced by a phone speaker shows how fragile mastery can be. But it’s that fragility that makes it beautiful. In the end, a watch’s defiance against magnetism is really a story about balance — between order and disorder, between human ambition and natural law.

Modern watchmakers continue to play with that theme, not just technically but symbolically. Omega’s Master Chronometer Certification, for example, tests watches up to 15,000 gauss — a level so extreme it borders on theatrical. It’s not that anyone will ever encounter that field in daily life; it’s that the number itself sounds heroic. It reassures you that your watch is tougher than you are. In doing so, it connects directly to that old 1950s spirit — the optimism that science could tame even the unseen. You’ll find the same story echoed in TAG Heuer’s Isograph concept, Rolex’s continued refinement of the Milgauss, and smaller independents quietly experimenting with non-ferrous escapements. Every brand, in its own way, is still trying to master what can’t be seen, because that mastery still sells trust.

If there’s one irony in all this, it’s that quartz watches — which are entirely immune to magnetism’s effects on balance springs — arrived just as the mechanical world perfected its defence. By the time silicon became the new saviour, the industry had already split between the old and the electronic. And yet, even as we wear smartwatches wrapped in Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, the mechanical world continues to evolve its anti-magnetic defences with almost stubborn pride. Because at heart, the fight against magnetism isn’t just about protecting accuracy — it’s about preserving identity. A mechanical watch, by its very nature, insists on being affected by the world. The goal isn’t to escape physics; it’s to overcome it gracefully.

Perhaps that’s why collectors still care so deeply. When you buy an anti-magnetic watch today, you’re not just buying protection from a fridge magnet; you’re buying a piece of history — a chapter of humankind’s relationship with the unseen. It’s one of those stories where engineering meets philosophy. The same invisible field that can derail a train’s compass or corrupt a hard drive can also make a person fall in love with the elegance of resistance. Because every time you glance at a watch that’s quietly defying magnetism, you’re reminded of the invisible choreography happening beneath that dial — the balance wheel oscillating in perfect rhythm, utterly indifferent to the chaos around it.

And that’s really what makes magnetism so compelling in horology. It’s not just about precision or performance; it’s about poetry. We live in a world drowning in invisible forces — magnetic, digital, emotional — and yet, on our wrists, we wear machines that defy them, quietly and without complaint. The next time your watch ticks perfectly through the hum of a train station or sits calmly beside your laptop, take a second to appreciate what’s really happening. You’re not just keeping time. You’re wearing one of humanity’s quietest victories — a small, spinning declaration that even the unseen can be understood, mastered, and made to serve the rhythm of our lives.

The Science Beneath the Spell

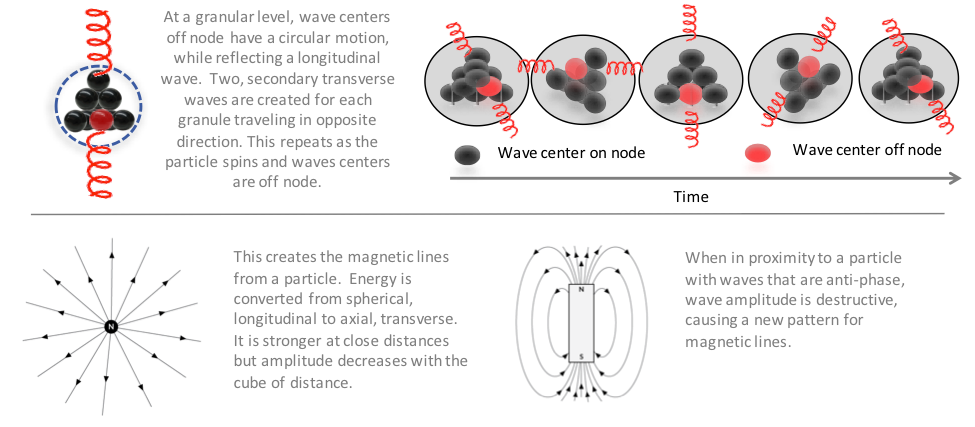

The more we talk about magnetism in watchmaking, the more it starts to sound like myth — an invisible enemy, an unseen war, a quiet triumph. But underneath all that, poetry is a very real science. To understand how magnetism affects a watch, you have to step into the world of atoms, electrons, and energy fields. The irony is that the same physics that keeps your fridge door closed is the same force that can throw your meticulously regulated chronometer into chaos. It all comes down to how matter behaves when exposed to a magnetic field — and how horology learned to dance around it.

At its simplest, magnetism is the result of moving electric charges. Every atom contains electrons spinning around its nucleus, each creating a tiny magnetic field. In most materials, those microscopic fields cancel each other out because the electrons are randomly oriented. But in ferromagnetic metals — like iron, nickel, or cobalt — the fields can align, forming regions called domains that point in the same direction. When enough of these domains line up, the material becomes magnetised. In a watch movement, that’s where the trouble begins. Components like screws, levers, pivots, and especially the hairspring are often made of alloys containing iron or nickel. When these parts enter a magnetic field, their atomic domains can become partially aligned, turning them into miniature magnets themselves.

That’s where the domino effect starts. The balance spring, that tiny coil of precision, begins to stick to itself. Adjacent coils cling together through magnetic attraction, shortening the effective length of the spring. A shorter spring oscillates faster, which makes the watch gain time. Sometimes a mild magnetisation will only cause a few seconds of deviation; in stronger cases, it can add minutes per day. The effect is cumulative and subtle — the watch doesn’t seize up, it simply starts lying to you. The longer it stays magnetised, the more unpredictable it becomes.

What most people don’t realise is how surprisingly weak the magnetic fields need to be to cause trouble. We measure magnetic flux density in gauss (named after Carl Friedrich Gauss, the mathematician who defined the measurement system). The Earth’s magnetic field, for instance, is about half a gauss. A basic household magnet can reach around 100 gauss, while the average smartphone speaker can produce several hundred. Many vintage watches from the early 20th century could be disturbed by as little as 50 gauss. That’s why a laptop’s magnetic clasp or a handbag closure can so easily send an older mechanical watch haywire.

The industry quickly realised it needed standards to define resistance. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) eventually set the bar: for a watch to be labelled “antimagnetic,” it must resist exposure to a direct field of 4,800 A/m (roughly 60 gauss) without deviating by more than 30 seconds per day. It’s a modest threshold by today’s standards, but for decades it served as the baseline. The heavyweights like Rolex, Omega, and IWC soon raised their own limits — first 1,000 gauss, then 15,000, until “antimagnetic” became almost a competition of courage. Omega’s Master Chronometer watches, for example, can endure 15,000 gauss thanks to silicon balance springs and non-ferrous components. For context, that’s stronger than the magnetic field of an MRI scanner. You could literally wear one inside a hospital imaging suite without losing accuracy — not that anyone recommends testing it.

The traditional way of protecting movements was by shielding rather than changing materials. Enter the soft iron inner case, or the “Faraday cage.” The principle is delightfully simple: if you can’t stop the magnetic field, you redirect it. Soft iron — a highly permeable material — conducts magnetic flux around the movement, creating a closed loop that diverts the field lines away from sensitive parts. It doesn’t eliminate magnetism, it just gives it somewhere else to go. The caseback, mid-case, and dial form the enclosure, essentially building a miniature magnetic tunnel around the calibre. The watch remains safe inside its cocoon.

But shielding had its limits. It added thickness and weight, and it meant the watch couldn’t have a display back — a serious aesthetic sacrifice as collectors grew to appreciate open case designs. It also couldn’t handle extreme fields. That’s where material science stepped in, with alloys like Nivarox and Elinvar, developed in the early to mid-20th century. These alloys reduced sensitivity by minimising the magnetic properties of the balance spring, while also stabilising it against temperature fluctuations — another invisible enemy. For decades, Nivarox became the standard hairspring material used by nearly every Swiss manufacturer, until the next revolution came along: silicon.

Silicon changed everything, not just because it’s antimagnetic, but because it allowed precision on an atomic level. Made using photolithography — the same process used to create microchips — a silicon hairspring isn’t milled or shaped by hand; it’s etched at a microscopic scale. That means no mechanical stress, no memory deformation, and absolute uniformity. More importantly, silicon is a semiconductor, meaning it doesn’t carry a magnetic domain structure at all. Magnetic fields pass through it without effect. The result is complete immunity to magnetism, combined with incredible stability and elasticity. It’s light, corrosion-resistant, and never needs lubrication. The only real downside is cost and fragility — once broken, it can’t be repaired like traditional metals. But in terms of precision, it’s as close to perfection as watchmaking has ever come.

Even so, the science of demagnetisation remains essential. Because no matter how advanced your movement, magnetism creeps in where you least expect it. That’s why most watchmakers keep a demagnetiser on the bench — a small device that generates an alternating electromagnetic field. When a magnetised watch is passed through it, the alternating polarity gradually randomises the magnetic domains in the metal parts, cancelling their alignment. It’s the horological equivalent of shaking a snow globe until the flakes settle. The process takes seconds, but it’s oddly satisfying — the modern exorcism of the mechanical world.

And it’s not just for professionals anymore. Affordable demagnetisers have become a household tool for enthusiasts. A few seconds under that pulsing field can transform a watch running minutes fast back into one that’s spot-on. The experience tends to leave people quietly amazed, especially those who’ve spent days trying to adjust the regulator before realising the problem was invisible all along. It’s a gentle reminder that sometimes, the fault isn’t in the craftsmanship — it’s in the air around us.

The deeper you go into this subject, the more it becomes clear how elegantly horology sits between physics and philosophy. Every advancement against magnetism is both scientific and symbolic. It represents mankind’s attempt to bring order to the unseen — to make time itself immune to interference. From the early palladium balance springs to silicon’s microscopic perfection, the journey reads like a chronicle of our evolving relationship with technology. It’s one of those quiet stories that connect the Enlightenment to the Information Age, carried on the wrist of anyone who loves the feel of ticking gears over glowing screens.

And yet, magnetism remains one of the most humbling forces in horology. It’s the constant reminder that perfection will always exist just out of reach. Even the most advanced materials have limits; even the best-engineered movement can be thrown off by something as ordinary as a fridge magnet. But maybe that’s part of the charm. Because what makes mechanical watches so enduring isn’t their immunity to nature — it’s their defiance of it. Magnetism simply adds another layer to that defiance: invisible, unpredictable, and beautifully human.

…and in that sense, anti-magnetism became a cultural statement about self-control, resilience, and quiet mastery. You could almost sense the symbolism radiating from those dials: an invisible strength against an invisible threat. For engineers, physicists, and technicians of the post-war age, it wasn’t vanity—it was validation. The world was becoming noisier, more electric, more uncertain, and to wear something that could stay truthful to time despite the chaos was oddly comforting. It said: the world may hum with interference, but I remain steady.

What makes this even more fascinating is how design itself began to adapt to that sentiment. Early antimagnetic watches were usually understated, because their purpose wasn’t glamour but function. Yet as decades passed, that quiet confidence evolved into an aesthetic all its own. The thick dials and closed casebacks necessitated by soft-iron shielding gave these watches a certain visual gravity—a feeling of robustness and intellect. The Omega Railmaster’s plain, legible dial, the IWC Ingenieur’s geometric precision, and the Rolex Milgauss’s iconic lightning-bolt seconds hand all told their stories without words. Each element existed for a reason, and each reinforced the notion that a watch built for magnetic resistance was a watch built for purpose.

Even colour played a role in this silent conversation. The orange flashes on the Milgauss or the warm lume of early Railmasters added subtle personality to what might otherwise have been austere instruments. They signified energy, precision, and presence—a subtle nod to the scientific environments they were designed for. A generation later, collectors began to see these watches not just as tools but as time capsules of an era when science and style first began to merge on the wrist.

Yet beneath all that aesthetic refinement, the science kept moving. When silicon entered the conversation in the early 2000s, it changed everything again. Silicon isn’t merely antimagnetic—it’s magnetically indifferent. It doesn’t care whether it sits beside a loudspeaker or a particle accelerator; its properties remain unaltered. That innovation allowed brands to shed the Faraday cage entirely and re-embrace open casebacks, lighter designs, and thinner profiles. Suddenly, resistance didn’t require compromise. Omega’s Co-Axial calibres, Patek Philippe’s Spiromax balance springs, and Breguet’s silicon overcoils weren’t just improvements—they were the end of magnetism as a mechanical threat.

But of course, horology being what it is, the victory wasn’t only technical. Once the threat had been conquered, the romance of the struggle became part of watch culture. Modern collectors often speak with affection about the days when magnetism still felt dangerous, when a stray speaker or airport gate could “possess” a movement. In a strange way, magnetism has become part of horology’s folklore—the villain that taught watchmakers to think differently, the unseen antagonist that made heroes out of engineers.

And in truth, the story never really ends. Today’s silicon components may laugh in the face of ordinary magnetic fields, but the environments around us are intensifying. The modern world now hums with Wi-Fi routers, induction hobs, electric cars, magnetic clasped laptop cases, and ever-stronger wireless chargers. We live in a soup of invisible energy that Michael Faraday could scarcely have imagined. And yet, your wristwatch ticks on. There’s something beautifully human about that image—a centuries-old craft surviving, adapting, and thriving amid forces that no eye can see.

If anything, magnetism’s legacy is larger than its science. It taught horology to respect the unseen, to prepare for the forces we cannot sense but which quietly shape the world. It pushed materials science forward, inspired design evolution, and fuelled decades of innovation. But it also shaped the very identity of the wristwatch. It made the mechanical watch not just an object of precision, but a declaration of resilience—proof that something so delicate could withstand an age of machines.

And perhaps that’s the real takeaway. Magnetism in horology isn’t merely a technical challenge overcome—it’s a parable of adaptation. From palladium hairsprings and iron cages to the serene defiance of silicon, every chapter reflects humanity’s determination to outthink its environment. The next frontier, as materials evolve and micro-engineering pushes boundaries even further, might see the mechanical watch exist in perfect harmony with the magnetic world rather than in conflict with it.

Until then, each tick of a watch that has resisted the pull of magnetism carries a quiet triumph. It’s the heartbeat of invention, the whisper of centuries of curiosity and persistence. And as long as those invisible fields continue to swirl around us, the story of magnetism in watchmaking will never be fully complete—because every generation of watchmakers will face the same question anew: how do we keep time honest in a world where everything pulls at it?

Just About Watches

Just About Watches