Now, plenty of people in watchmaking are content trudging along the road that’s been paved ahead of them. Tradition gets a bad rap these days, but there’s a quiet nobility in stewardship, in carrying the old flame into new rooms. Still, there are others—and I tend to gravitate toward their kind—who bristle against the expected, who itch to explore the unfamiliar, who leave an almost poetic wake of solder, oil, and curiosity behind them. Rare still are those who don’t just choose a different path, but dig deep and remodel the terrain itself. Peter Speake isn’t just a good example—he’s practically the blueprint for transformation, and in my mind, that’s far more interesting than shock or spectacle.

When I first came across Peter’s work, what caught me, probably before even the details of his watches, was that sense of quiet courage. He doesn’t announce his presence in horology with fireworks and clever branding. Instead, there’s this understated persistence—like he’s humming in a lower register while everyone else tries to hit the high notes. And I find myself really drawn to that. In any pursuit, but especially one as relentless as watchmaking, it takes guts to avoid the shouting match and trust the resonance of your own voice. You don’t need to blast, just to be heard by those who are really listening.

Peter’s story begins far from the hallowed hexagons of Switzerland—in Essex, of all places, in 1968. Essex isn’t the sort of place you’d expect to breed a watchmaker of high regard. More known for commuter trains and coastline than for horological royalty. Yet I can’t help thinking that this distance, this lack of connection to the sacred valleys, is partly what gave him an edge. Sometimes it’s the outsider who sees clearest; when you start away from the system, you see what it does well, but also where it trips over its own legends.

He started off, like so many of us, with a simple fascination for how things worked. I see a bit of myself in that urge—turning it over and over in your mind until curiosity settles into something more deliberate. That trajectory took him to Hackney Technical College. Not exactly the stuff of glossy alumni lists, but the perfect ground for anyone who values craftsmanship for its own sake. It’s the kind of place that doesn’t encourage shortcuts; you pick up patience there, and patience is a rare gift. I sometimes wonder whether the most powerful things we learn aren’t the ones that seem glamorous, but the ones that teach us to endure, to persist.

What’s interesting about Peter’s time at Hackney is how it shaped his sense of repetition—the slow, meditative building of skill. It doesn’t get talked about much, but I think joy in repetition is what gives any creative act its backbone. Watchmaking, above all, is about earning muscle memory: the thousandth attempt is not just as necessary as the first, but more so. Peter soaked that up, and it formed the scaffolding of a philosophy he’d carry with him: mastery starts with practice, not epiphany. I connect with that—none of my best work was ever a sudden lightning strike, but rather a slow-growing canopy-built day by day.

From Hackney, he made the leap to WOSTEP in Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Now, for watchmakers, WOSTEP is somewhere between Hogwarts and the Shaolin temple of horological discipline. You don’t just learn to file a bridge; you learn reverence for the invisible—the bevel that’s hidden beneath the dial, the labour only you know exists. There’s a beautiful humility in that. Modern life wants everything in plain view, loud and proud, but WOSTEP teaches that the secret parts deserve the same care as the ones that catch the light. That’s spiritual as much as technical—and when Peter left, he wasn’t just a better “doer” of watchmaking, he’d caught the soulful side of the trade as well.

London lured him back, and with a little serendipity, he joined Somlo Antiques. Somlo isn’t merely a shop; it’s almost a living museum, a crossroads where past and present shake hands. If you want to know how much a person values history, watch them restoring a marine chronometer from the age of sail, or coaxing a Breguet pocket watch back to beat after centuries of silence. That was Peter’s daily fare. In those details, you don’t just encounter the watch; you step into the mind of the last person to touch it, hundreds of years ago. Doing this work leaves a mark. It’s a humbling thing, conversing across centuries and coming away knowing that someone, somewhere, had surer hands on a bad day than you do on your best. It puts pride in its place.

But restoration, as much as I deeply respect it—and I do—can be a cage as well as a calling. Peter, who is clearly wired to invent rather than imitate, felt that weight. There comes a moment for any creative, I think, when you realise you want to make your own mark, not just keep someone else’s alive. So he pivoted—back to Switzerland again, this time to Renaud & Papi (the bit of Audemars Piguet dedicated to the truly wild stuff). If the rest of watchmaking is the first act, Renaud & Papi is where the curtain rises on the main event: tourbillons, minute repeaters, and complications that most of us can only dream of dissecting. This was watchmaking at the bleeding edge.

For Peter, Renaud & Papi was a crucible. It wasn’t about ticking the boxes; it was about burning away everything unnecessary, boiling it down until only the essential remained. Every choice was an argument with steel and brass—a constant intellectual battle. And as much as it honed his hands, it also polished something deeper: an emotional commitment to structure, to architecture. Watches are buildings in miniature; when you know that, you build for proportion. Peter’s later works always reflect that—never a screw without intent, never a flourish without scaffolding to hold it up.

Then comes the part I admire most in anyone’s journey—the leap of faith. 2000—Peter leaves the certainty of ateliers and brand reputations to strike out on his own. No safety net, no huge marketing budget, no celebrity endorsements. I think about that sometimes: in a risk-averse world, it’s even bolder to make something honest and put your name on it. His pieces from those early years didn’t knock on doors; they opened them quietly and waited for the right people to step inside. I see that same trait in those I most respect—if the craft is solid, it doesn’t need a sales pitch.

The Foundation Watch—there’s poetry in that name—became his signature. If Peter ever had a statement of belief, this was it, both a technical achievement and a declaration: every part, visible or not, polished by hand, built for longevity and clarity. There’s a specific kind of beauty to a watch that is as lovely inside as it is outside. I think it’s because you sense it as an integrated thing, not a surface for passing pleasure. For Peter, and for those of us who appreciate the philosophy behind the object, a watch isn’t a trophy. It’s a kept promise, an ecosystem where nothing gets neglected. It reminds me of the best traditions in English and Swiss craft—functional but poetic, quiet but confident, a nod to the past without being held hostage by it. That’s a lesson I try to fold into everything I make or do: honour what’s come before, but don’t get shackled by it.

Peter didn’t flinch as the years rolled on and others chased trends. He didn’t try and get louder; he kept refining. I find that approach deeply grounding. There’s something calming about people (and objects) that move at their own pace, defining their evolution not by fads but by conversation—with their own history, with their materials, with the people who will live with their work. Peter’s dialogue—between British solidity and Swiss finesse, architectural certainty and fine finishing—shows what can happen when you synthesise traditions instead of picking sides. In his watches, heavy lugs echo English manufacture, while delicate finishing whispers of Swiss apprenticeship. That sort of fusion doesn’t happen by accident; it happens when someone is honest about where they come from and where they’re trying to go. That honesty is increasingly rare.

Behind closed doors—often, the most instructive spaces—Peter’s always had a philosophical bent. For him, watchmaking goes well beyond an occupation. Every adjustment, every file stroke is a kind of meditation. I can’t help but nod along—the most meaningful work I do is always the work that forces me to slow down and be fully present. He talks about discipline as a form of peace, not punishment. There’s humility built into every bridge bevelled by hand, every hairspring nudged into tolerance. Perfection isn’t an event; it’s a practice—a habit of attention.

And that’s why his next move strikes me as one of the boldest: after years at the head of an independent brand, he let it go. Most people spend their lives stitching their identity to the flagships they build; Peter had the seriousness to walk away and try something entirely new, not with product but with knowledge. Cue The Naked Watchmaker—a concept that, looking back, seems almost inevitable and entirely right. Now, instead of building watches, he stripped them bare—revealing the bones not for show, but for understanding. I love this phase best, I think. Not everyone can admit they want to teach, but Peter did, and with that came a new clarity to his work: the clarity of a man unconcerned with mystery and myth-making, and focused instead on showing the world how things really work.

If there’s a heart to his educational philosophy, it’s that revelation breeds appreciation, not demystification for its own sake. Clear, methodical photography, patient explanations, reverence for both the cheap and the priceless—each guides the student to see watches as systems, as purposeful constructions worth more than marketing can ever suggest. It’s not about diminishing the magic. Instead, it’s about making us realise how magical good engineering really is. His humility in this role—never showing off, always inviting curiosity—feels radical in an age starved of genuine humility.

Most watchmakers hide behind their mythos, never letting anyone see how the sausage is made. Peter does the opposite. He’s not aiming for celebrity or even thought-leader status. He’s more like a guide who doesn’t mind whether you’re already a convert or just curious. In a world saturated with watch hype, status symbols, auction records, and a culture obsessed with scarcity, his insistence on calm explanation feels almost revolutionary. He reminds me (and should remind everyone) that horology, at its best, isn’t about what you can show off—it’s about what you can learn, what you can make, what you can care for.

There’s something endearingly human in Peter’s curiosity. When he strips a Patek or a De Bethune, it’s not about rivalry—it’s about admiration, about learning irrespective of reputation. To me, that’s legacy: not mastery enshrined forever, but curiosity never abandoned.

So much of the talk about independent watchmaking is rooted in numbers—limited pieces, exclusive workshops, ornate finishing. I think Peter—and I—see independence differently. It’s not size, it’s autonomy. It’s being stubborn enough to chase your truth, whether it’s building a tourbillon, a simple three-hand, or just showing people what’s inside. That’s what I want in my own work: the force to follow an idea wherever it leads.

The most beautiful part of Peter’s journey, as I see it, is the quiet consistency that stitches every phase together. The boy from Essex repairing clocks hasn’t vanished—he’s simply evolved. Whether he’s restoring, creating, or deconstructing, each phase is an echo of the last, the rhythm of a balance wheel repeating its purposeful motion. Rhythm! That’s what keeps coming back to me: the rhythm of patience, deceleration, and knowing when to let go.

In a world that worships speed, Peter’s path is one of deliberation—I aspire to that. Each decision, each piece, each pivot in his career, lands with intent, like the gentle tick of a perfectly adjusted escapement. When I study his story and his methods—his teaching, photography, thoughtfulness—I’m reminded of what drew me to craft to begin with: the wanting to know why, not just how, things work. To look just a little deeper, to find meaning in the process, not just the product. That’s where I want my own stories to be told.

So when you strip away all the layers—the marketing, the prestige, the speculative fever—what’s left is a handful of people who truly understand what they’re doing, and why it matters. Peter Speake stands among those rare few. He’s drawn every arc in horology’s story: restoration, creation, interpretation. Through it all, his example whispers to those who are listening: watchmaking isn’t the act of measuring time, but of spending it, and spending it well. That’s a lesson I intend to take to heart.

And here’s why that matters: in the end, the real worth in a craft isn’t found in fame or fortune, but in faith—in the work itself, in the discipline of knowledge, in trusting that even as machines get smarter and automation spreads, the human hand and the human eye still have a place. That constancy, that idea that the mechanism is a metaphor for life—complex, fragile, enduring if kept with care—rings true whether you’re making watches or making meaning in any form.

When I look at Peter Speake’s story, what I see most clearly is a kind of independence that I value deeply: not isolation, but authenticity; not the need to go it alone, but the refusal to think in anyone else’s terms. He’s shaped not just timepieces, but the way people like me see the whole idea of craft and creation. That, in my book, is his most revolutionary act—and the one I aspire to in my own work, every time I sit down at the bench, the desk, or the page.

All these crossroads and reinventions wouldn’t count for much, of course, without the tangible milestones—the watches themselves, the impact he’s had on the industry, the ripples others have felt.

Talk to anyone in the know, and sooner or later, they bring up the Foundation Watch. I think it’s fair to say this is where Peter truly planted his flag—an uncompromising piece that declared, “This is what I stand for: mechanical purity and honest craft.” The Foundation Watch wasn’t just an exercise in complexity; it was proof that a timepiece could be both deeply traditional and quietly radical. Hand-finished throughout, inside and out, its movement was so meticulously designed that even the parts only a watchmaker would ever see were given the full measure of care. You can feel it—almost sense Peter’s presence—each time you turn one of those pieces over in your hands.

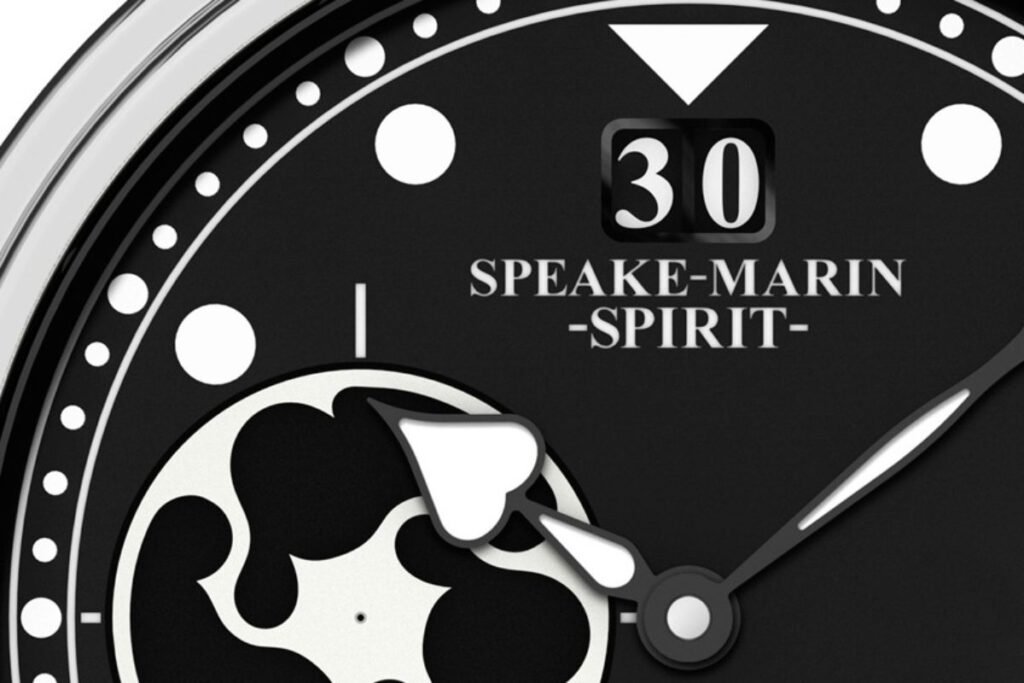

But he didn’t stop there. The Open Dial—which became a signature feature for his brand—did what so many watches promise (but few deliver): it made the intricate workings visible without showboating. Rather than screaming for attention, it invited a kind of quiet contemplation. It’s the sort of thing that, if you’re anything like me, you find yourself studying in the oddest light, tilting your wrist and watching the dance of the gear train, the interplay of levers and wheels.

Of course, any conversation about Speake’s career would be incomplete without mentioning his remarkable collaboration with Daniel Roth, one of the living legends of the craft. That partnership didn’t just result in memorable watches; it brought together two philosophies—French and English traditions in design, with Swiss refinement—meeting somewhere in the middle, making the kind of watches that are whispered about for years in collectors’ circles. Their work on constant force mechanisms, and the tourbillon especially, wasn’t just about technical gymnastics. If you’ve seen their tourbillon, you’ll know what I mean: there’s a poise to it, an architectural neatness, like it was engineered by someone who carries architecture in their blood.

Then there’s the work at Renaud & Papi. We sometimes forget that before independent fame, Peter was in the trenches of complication. He was instrumental in the development of pieces that are benchmarks now—grand complications for Audemars Piguet, mind-bending minute repeaters that still have veteran watchmakers shaking their heads in admiration. When the industry’s best wanted something wild—something that would push both the limits of engineering and aesthetics—they came to Peter and his team.

After going independent, he didn’t just launch the Speake-Marin brand—he built it up to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the world’s best before stepping away (an achievement in itself, to know when to move on, to have the courage to let your creation live without you at the helm). Watches like the Piccadilly, the Serpent Calendar, and the Spirit Wing Commander all tell a story of a watchmaker who can balance classic English cues with modern confidence. The Piccadilly’s case alone deserves an essay: architectural, robust, and instantly recognisable, it’s one of those designs that makes you wonder why nobody tried it before.

Stepping outside traditional watchmaking, Peter’s “Naked Watchmaker” venture is probably his boldest and most generous achievement. It’s no small act of courage—or humility—to lay bare the secrets of your trade. Yet he’s done more to demystify mechanical watchmaking for ordinary enthusiasts than any marketing department ever could. His educational platform has become a reference for collectors, students, and even his peers.

If achievements are measured in ripple effects, then countless contemporary makers owe something to Peter’s example—the infectious enthusiasm, the integrity, and above all, the willingness to value transparency over mystique. Trace back the growing movement of honest, educational watchmaking, and you’ll find Peter’s fingerprints, even where his name is absent.

When people talk about legacy, I think of Peter’s contributions not as trophies lined up on a shelf, but as tools—or even better, seeds. He’s cultivated not only remarkable watches, but remarkable conversations—about what matters in this world of micro-mechanics, about why doing things properly still counts, and about why time, in the end, is best spent in the service of something genuine.

I’ll be going into detail with Peters’ success after the Naked Watchmaker soon enough….

Just About Watches

Just About Watches