A watch is rarely just a watch. It might be a sentimental heirloom, an investment-grade collectable, a reward for years of hard work, or a mechanical companion worn every day. The emotional weight behind each piece complicates the decision to insure it, because what you stand to lose is never fully captured in money. Yet, paradoxically, insurance is all about money—about calculating premiums, payouts, exclusions, and costs over time. This tension between economics and emotion is what makes watch insurance such a fascinating and polarising subject.

The arithmetic is the most obvious starting point. Most dedicated watch insurance policies, whether standalone or attached to a home insurance rider, typically fall within the range of one to two per cent of the insured value per year. That means insuring a £10,000 watch will cost you £100 to £200 annually. For one watch, this may feel manageable—especially if that watch is the crown jewel of your collection. But when collections grow, so does the premium.

Ten watches valued at £10,000 each? Suddenly, you’re paying £1,000 to £2,000 per year. A collection valued at £250,000, not unusual among seasoned enthusiasts, could easily incur premiums of £3,000 to £5,000 annually. That’s the cost of a respectable new watch every year, evaporating into the ether for protection you may never use. Compounding makes the numbers even starker. Imagine insuring that £100,000 collection at 1.5% annually. Over ten years, assuming no claims, you’ll have paid £15,000—enough to buy a vintage Daytona or two Grand Seiko Spring Drives. Over thirty years, the total soars past £45,000. At that point, the premiums themselves could represent an entire collection. This is where the opportunity cost argument gains traction: insurance money, if invested or spent differently, could significantly expand or enrich your horological journey. Still, arithmetic alone can’t settle the debate. Because while the cost is measurable, the benefit is conditional. Insurance only becomes tangible when disaster strikes, and therein lies the paradox: the best case is that you never need it.

Many collectors assume their home insurance will suffice. And technically, in many cases, it does—at least partially. Standard home policies typically cover valuables like jewellery and watches against fire, burglary, or major household disasters. But the limitations are often crippling. Coverage may only apply within the home, or “personal possessions” add-ons may cap compensation at a per-item limit, often £1,500 to £2,500. That barely scratches the surface of even an entry-level luxury piece, let alone a rare or vintage model. There’s also the question of proof. A kitchen fire that destroys a watch box may be straightforward to claim, but theft claims often trigger far more scrutiny. Did you keep receipts? Do you have high-resolution, time-stamped photographs? Was the watch valued recently? Many insurers demand independent valuations every one to three years, particularly for vintage pieces, to ensure the declared value reflects current market conditions. That appraisal process can cost £50 to £150 per watch each time, adding hidden expenses that few enthusiasts factor into their calculations.

This is why many collectors migrate to specialist insurers like TH March, Hiscox, or Chubb. These companies understand the nuances of horology. They recognise that a 1965 gilt-dial Submariner isn’t just another Rolex but a piece with specific collector value. They are more likely to offer agreed-value policies, where payout amounts are locked in advance, sparing you from post-loss valuation disputes. Some even offer new-for-old replacement guarantees, sourcing equivalents from the secondary market rather than offering a modern substitute. Naturally, such specialist coverage commands higher premiums, but for serious collectors, the peace of mind is often worth the added cost.

The most important economic factor isn’t the annual premium—it’s whether the insurer pays out when you need them. This is where the divergence between policy theory and claims reality becomes dramatic. Positive stories exist. Collectors report losing watches abroad and receiving full payouts within weeks, thanks to meticulous records. In these cases, insurance does exactly what it promises: it restores value quickly and without trauma. But there are also horror stories. Insurers are disputing ownership because receipts were lost. Claims were delayed for months while underwriters scrutinised photographs. Payouts were reduced because market values had shifted since the last appraisal. Worse still are the mismatched replacements. One collector reported that after his vintage Datejust with a tritium dial was stolen, his insurer offered a brand-new Datejust as a replacement. To a generalist, the two are functionally identical. To a collector, they are galaxies apart in character and value. The economic lesson is simple: unless your policy explicitly stipulates agreed value and collector-sensitive replacement, you may not receive what you truly lost. And if what you lost was a story as much as a watch, no payout can fully restore it.

This leads naturally to the idea of opportunity cost and self-insurance. Over decades, the cost of premiums can dwarf the value of any single claim. Some collectors wonder if they would be better off insuring themselves. The self-insurance model is straightforward: instead of paying premiums to an insurer, you set aside an equivalent sum each year in a dedicated fund. If disaster strikes, the fund covers part of the loss. If nothing happens, the fund grows—and eventually may be large enough to absorb a significant hit. For example, a collector with a £50,000 portfolio paying £750 annually at one and a half percent could, after 20 years, accumulate £15,000 in a self-insurance account. That’s not enough to replace the whole collection, but it could cushion a loss or supplement other resources. This approach requires discipline—few collectors reliably set aside premiums year after year without fail. It also requires emotional detachment. If you lose a £20,000 watch but only have £15,000 saved, you must accept partial restitution. Still, for collectors with diversified portfolios or lower-risk lifestyles, self-insurance can be an economically rational choice.

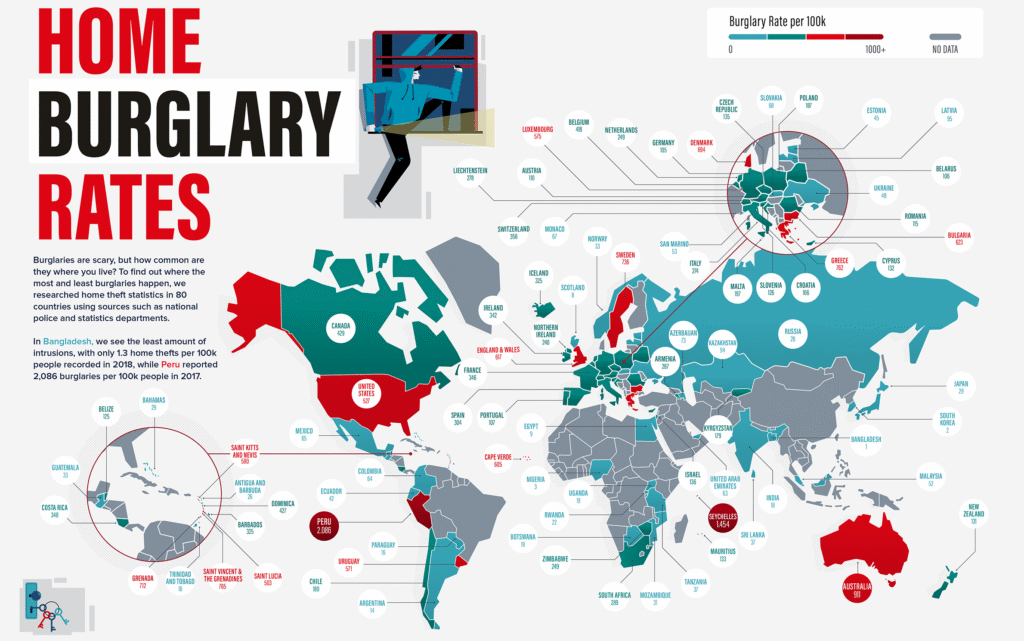

Insurance culture also varies by geography, and understanding these differences shapes expectations. In the UK and Europe, specialist watch policies are relatively common, with firms like TH March catering to both jewellers and private collectors. Policies tend to emphasise agreed values and travel coverage. In the US, homeowners’ policies dominate, but add-ons like scheduled personal property riders are required for higher-value items. American insurers like Jewelers Mutual cater to collectors, but uptake is less universal than in the UK. In Asia, the picture is mixed. Japan’s conservative insurance market often treats watches more as personal property than collectibles, with limited specialist offerings. Hong Kong and Singapore, as global watch hubs, see greater use of specialised coverage, particularly among high-net-worth individuals with multi-million-dollar collections. Cultural attitudes also play a role: in some regions, the expectation of personal vigilance and safe storage replaces reliance on insurers.

One of the most fascinating psychological effects of insurance is how it changes behaviour. Some collectors avoid wearing their most valuable pieces because they are uninsured, effectively locking their watches away. Others take out insurance yet still avoid certain situations—crowds, travel, or nightlife—because they distrust the claim process. Ironically, both groups lose out. Watches are designed to be worn, lived with, and embedded in experience. If insurance or lack thereof prevents that, then its economic and emotional cost is higher than the premium itself. At its best, insurance should liberate you to wear your watches without fear. At its worst, it creates another layer of anxiety. Understanding which effect it has on you personally is crucial in deciding whether the premiums are worthwhile.

The psychology of risk and peace of mind cannot be separated from the economics. For some, peace of mind is priceless. Knowing that their grail piece is protected allows them to wear it without hesitation. For these collectors, the annual cost is not an overhead—it is an enabler of joy. For others, paying year after year without claiming feels like a constant drain, a tax on passion. These collectors may prefer to accept risk and invest their money in tangible enjoyment—new acquisitions, servicing, or accessories. Neither approach is objectively superior. The true answer lies in personal temperament. Are you the type to lose sleep over exposure? Or the type to shrug and embrace fate? In the world of horology, both mentalities exist, and both are rational responses to uncertainty.

The emerging frontier of smartwatches complicates the picture further. AppleCare+ now includes theft and loss coverage for the Apple Watch Ultra, a first for wearables. Other brands are beginning to follow. But the economics differ sharply from mechanical watches. A luxury mechanical watch may hold or increase in value over decades. A smartwatch depreciates rapidly, often losing half its retail value within two years. From a pure economic standpoint, insuring a smartwatch makes little sense. Yet smartwatches carry a different kind of value: digital data. Health metrics, authentication codes, payment systems, and even identity documents can live inside them. When a smartwatch is lost, the financial cost may be minor compared to the digital disruption. Traditional insurers have yet to fully account for this dual risk: hardware plus information. As the lines between mechanical artistry and digital utility blur, future insurance models will likely need to evolve to reflect this hybrid reality.

For those considering insurance today, certain practices maximise both protection and peace of mind. Keeping meticulous records is essential: receipts, high-quality photographs, and valuations should all be stored securely in both physical and digital formats. Regular valuations ensure that coverage reflects real-world market prices, which can fluctuate dramatically for vintage or sought-after pieces. Policy exclusions must be studied carefully, since many omit scenarios like unattended hotel theft or mysterious disappearance. Agreed-value coverage, where payout is locked in advance, eliminates disputes later. And finally, premiums should be balanced against usage. A watch that never leaves a safe may not require insurance at all, while one worn regularly on international travel may demand it.

In the end, the economics of watch insurance is not about right or wrong—it is about clarity. It forces each collector to confront the balance between numbers and narratives, between premiums and peace of mind. For some, insurance is essential, enabling freedom of wear and global travel. For others, it’s a quiet tax on sentimentality, an overhead that could be channelled into more tangible enjoyment. Perhaps the most profound lesson is that watches, even when viewed through the lens of insurance, resist being reduced to mere numbers. They remain artefacts of memory, markers of time, and carriers of story. Insurance can protect their market value, but it can’t replace their meaning. And in the end, that is where the economics of insurance meets the philosophy of horology: value, like time itself, is never entirely fixed.

Beyond Premiums – Risk, Behaviour, and the Hidden Economics of Horology

Insurance, in its essence, is an abstraction: a promise of financial restitution in exchange for a recurring payment. Yet in the world of watches, that abstraction intersects with desire, obsession, and identity in ways that few other asset classes experience. A watch is never merely an object of material value; it is a repository of memory, a mechanical confidant, and, for many collectors, a metric of personal accomplishment. This duality—practicality versus passion—makes the economics of insurance unique, nuanced, and at times, paradoxical.

For instance, consider the interplay between insurance and behavioural economics. Collectors often overestimate the probability of loss while undervaluing the opportunity cost of premiums. One might purchase a £250,000 collection policy for a relatively modest 1.5 percent annual premium, yet this decision compounds over decades into a sum approaching or surpassing the value of several high-end watches. Behavioural finance suggests that individuals are prone to “loss aversion,” a cognitive bias that makes potential loss feel twice as painful as equivalent gains. In horology, this translates into collectors prioritising coverage even when statistically, the likelihood of needing it is minimal. Insurers capitalise on this understanding, structuring products to appeal to emotional, rather than purely rational, considerations.

Conversely, there is a segment of collectors who consciously embrace risk. These individuals may opt for minimal coverage or self-insurance, reasoning that the financial and emotional overhead of full policies outweighs the potential payout. This risk-tolerant approach reflects a different facet of horological culture: ownership as engagement, not just protection. For them, watches are meant to be worn, experienced, and lived with. The anxiety of potential loss is accepted as part of the thrill of ownership. This philosophical stance aligns closely with the broader history of collecting: rarity, imperfection, and vulnerability contribute as much to value and satisfaction as monetary considerations.

Global market dynamics further complicate insurance economics. The secondary watch market has grown exponentially over the past two decades, with auction houses, online marketplaces, and private dealers driving rapid valuation shifts. A Rolex Daytona purchased at retail may double or triple in value within a few years. Similarly, limited-edition Patek Philippe complications can see meteoric appreciation, driven by scarcity and collector fervour. In such a fluid environment, fixed insurance premiums can lag behind reality. A policy written today at £10,000 coverage may be inadequate in two years if the piece appreciates significantly, forcing collectors to rebalance valuations and update policies frequently. These adjustments carry both financial and administrative costs, adding a hidden layer to the economics of insurance.

Insurance also interacts subtly with the psychology of wear. A fully insured watch may paradoxically become less cherished in daily experience. When a piece is insured and protected, the owner may treat it with clinical detachment, storing it carefully rather than embracing its intended purpose. Conversely, uninsured watches, by their very vulnerability, invite mindfulness and ritual. Winding, wearing, and observing a mechanical masterpiece becomes a conscious act of care. In this sense, insurance can alter not just financial risk but emotional engagement, subtly reshaping the relationship between collector and object.

Specialist insurers have responded by offering bespoke services that mitigate these tensions. Policies that account for agreed value, international travel, and even repair guarantees allow collectors to wear their watches without fear. Some firms provide concierge-level claims management, sourcing exact replacements from secondary markets or commissioning bespoke restorations. Others integrate risk-reduction advice: secure travel cases, tamper-proof storage, and regular maintenance checks. In effect, the economics of insurance is intertwined with operational risk management; the policy is just one component of a broader strategy to preserve value, usability, and enjoyment.

The role of provenance and documentation cannot be overstated. Watches with impeccable records—original box, papers, service history, and verified photographs—command higher resale prices and are easier to insure. Insurers often require annual reappraisals for vintage or investment-grade pieces, reflecting both market volatility and the scarcity of comparable examples. The expense of these appraisals, combined with storage, security, and maintenance, transforms what appears as a simple annual premium into a comprehensive cost of stewardship. Collectors must balance these expenses against the intangible benefits of peace of mind, a calculation that is as much philosophical as it is financial.

Travel and geographic considerations further illustrate the nuanced economics of insurance. International travel exposes watches to heightened risk: theft, loss, and accidental damage increase dramatically outside the familiar environment of home. Policies frequently include clauses that specify territorial limits, and claims often hinge on demonstrating due diligence—travel cases, secure storage, and adherence to recommended precautions. The rise of global watch tourism, luxury retail experiences, and collectors’ expos has made international coverage increasingly relevant. Without it, even the most meticulously insured collection at home remains vulnerable once it leaves familiar surroundings.

Emerging technology also intersects with this space. RFID tracking, GPS-enabled storage solutions, and blockchain-based provenance are beginning to redefine what it means to insure a watch. Imagine a watch with a microchip that transmits location, ownership, and service history to a secure digital ledger. In such a scenario, insurers could verify claims instantaneously, reducing administrative burden and accelerating payouts. Similarly, digital wallets and tokenised ownership could enable fractional insurance, where high-value pieces are covered by collective policies shared among multiple collectors or investors. While still nascent, these innovations hint at a future where watch insurance is not just protection, but part of a larger ecosystem of traceability, security, and investment management.

The economics of insurance also extend to emotional capital. A watch insured to its full value represents a collector’s acknowledgment of both its market and sentimental worth. The premium becomes a tangible expression of valuation beyond numbers—a marker of how much one is willing to invest to protect history, memory, and artistry. Conversely, the decision to self-insure or forgo coverage entirely reflects a different philosophy: ownership as experiential, acceptance of risk, and prioritisation of immediate engagement over theoretical protection. Both approaches, while materially distinct, share a common thread: they are conscious reflections on the value of time, craftsmanship, and personal connection.

Finally, the economics of watch insurance underscores a broader truth about horology itself: it’s not merely about clocks or watches, but about human relationships with objects that encapsulate skill, ambition, and legacy. Insurance quantifies risk, but it cannot measure joy, nostalgia, or admiration. Premiums are financial constructs, yet they intersect intimately with identity, pride, and the philosophy of ownership. Collectors, whether consciously or not, are negotiating these intersections every day, balancing cost, risk, and emotional resonance. In this sense, insurance is both a pragmatic tool and a mirror, reflecting how seriously we take our objects, our passions, and ourselves.

The lesson is clear: watch insurance is never purely economic. It is a negotiation between tangible value, intangible significance, and personal philosophy. The collector who approaches insurance thoughtfully gains more than protection: they gain clarity, understanding, and the freedom to experience their watches fully. Conversely, the collector who treats it as mere overhead may find the costs quietly eroding enjoyment, a constant reminder that even in the world of precise engineering, human choices define value. As horology continues to evolve, so too will the conversation around protection, risk, and ownership. And in that dialogue, we glimpse not just the economics of watches, but the enduring, subtle art of living with time itself.

Just About Watches

Just About Watches