The roots of this obsession stretch back to the early twentieth century, when the wristwatch was emerging as both a practical tool and a symbol of refinement. Vacheron Constantin and Audemars Piguet, among the foremost Swiss manufacturers, began experimenting with reduced-thickness movements to cater to a clientele that valued discretion and sophistication. Vacheron’s 1929 “Régulateur à tourbillon” and its later iteration, the calibre 1003, were remarkable achievements: a movement measuring just 1.64 millimetres thick, capable of keeping precise time while demonstrating a degree of refinement that was almost impossible to imagine at the time. Audemars Piguet, similarly, honed full-plate movements to exceptional levels of thinness, often supplying these movements to prestigious houses like Cartier and Tiffany, effectively becoming the hidden force behind some of the most elegant watches of the era. Jaeger-LeCoultre, dubbed “the watchmaker’s watchmaker,” was also a pioneer, producing calibres such as the 145 in 1907, which at 1.38 millimetres already seemed to defy the physical limitations of the materials available.

These early thin movements were primarily about refinement and craftsmanship rather than the pursuit of records. A watch that could slip easily under a cuff was an aesthetic and social statement. Yet, within the reduction of material lay the seeds of a more intense obsession. Each component, from bridges to pinions, required careful reconsideration; each gear had to justify its existence within a tighter space. Even then, watchmakers were learning to manipulate the invisible forces of torque, friction, and energy conservation in ways that would later become essential for record-breaking ultra-thin watches.

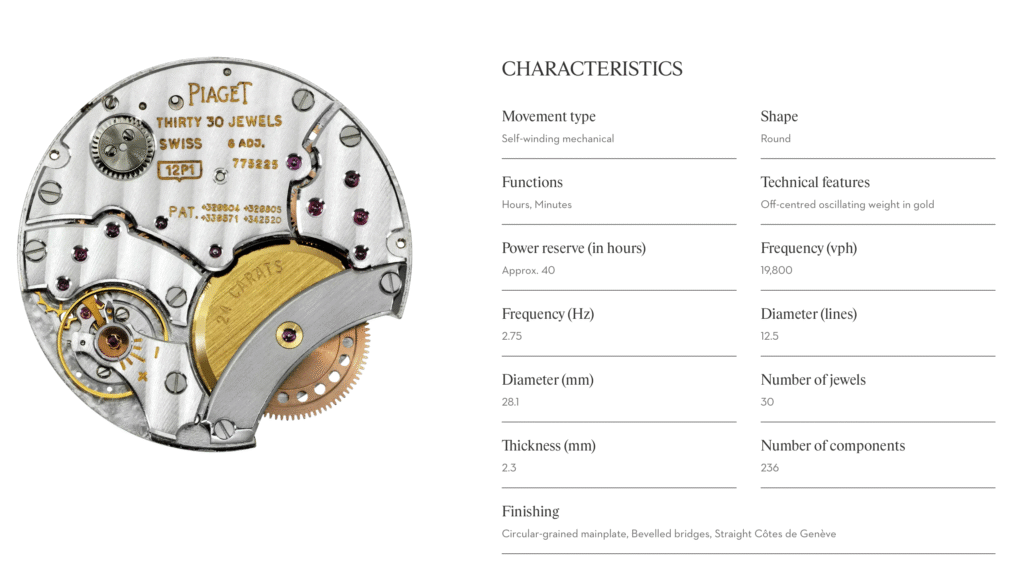

The mid-twentieth century marked the next evolution of this obsession. In 1957, Piaget introduced the calibre 9P, a manual-winding movement measuring a mere two millimetres thick. While modest by contemporary record-breaking standards, the 9P represented a quantum leap in mechanical design: bridges were thinner, wheels were delicately repositioned, and pivots were meticulously aligned to reduce unnecessary material. Piaget followed with the calibre 12P, an automatic micro-rotor movement measuring just 2.3 millimetres thick. Here, the rotor was integrated beneath the movement plate rather than above it, a radical design that required not only precision machining but also innovation in lubrication and gear meshing. This was more than thinness for elegance; it was the beginning of thinness as an intellectual and technical pursuit, a dialogue between materials, movement, architecture, and mechanical philosophy.

Jaeger-LeCoultre, Vacheron Constantin, and Audemars Piguet contributed parallel innovations during this period. Jaeger-LeCoultre’s calibre 849, for instance, demonstrated that manual-winding thinness could coexist with long-term reliability, while Audemars Piguet’s calibre 2120, later housed in the Royal Oak, combined thinness with robustness suitable for a sport-luxury watch. Vacheron’s 1003 continued to evolve, integrating shock-resistant features and improved torque distribution to ensure stability in an ultra-thin format. Collectively, these watches laid the foundation for what would later become the modern obsession: not merely a flat watch, but a record-breaking, engineering-defying statement that tested the limits of physics and materials.

The 1970s and 1980s brought a dramatic shift in the landscape of ultra-thin watchmaking, largely fuelled by the quartz revolution. Suddenly, the rules of mechanical thinness were challenged by entirely new technologies. While Swiss manufacturers had been quietly refining micro-engineering for decades, Japanese innovators such as Seiko and Citizen demonstrated that entire timekeeping mechanisms could be reduced to fractions of a millimetre by replacing wheels, pivots, and springs with miniature circuits, stepping motors, and polymer components.

Seiko’s Lassale line, introduced in 1977, showcased movements thinner than one millimetre. These watches achieved a delicate balance between elegance and technical ingenuity. By relying on printed circuits rather than traditional gear trains, and by integrating the stepping motor into the plate rather than on top of it, Seiko engineers created watches that were simultaneously revolutionary and commercially viable. Citizen followed suit with its Stiletto and Exceed Gold Leaf lines, marrying thinness with precision finishing. The components were so minuscule that conventional assembly tools could not be used; watchmakers often relied on microscopes, tweezers with extreme precision tips, and specially designed presses to position the micro-gears accurately.

Yet quartz thinness was fundamentally different from mechanical thinness. While the Japanese quartz watches dazzled with their slim profiles, they were not demonstrations of mechanical genius in the traditional sense. They relied on electricity rather than torque distribution, and they didn’t face the challenges of friction, power reserve, or escapement geometry that mechanical watches required. For purists, the real obsession with thinness remained firmly mechanical. The mechanical watch, after all, is an ecosystem of energy transfer: mainspring, wheels, escapement, balance, and hands all orchestrated in three dimensions. To reduce that system to near-flatness without sacrificing reliability, even for a few hours of daily wear, is a feat that engages the full spectrum of horological knowledge.

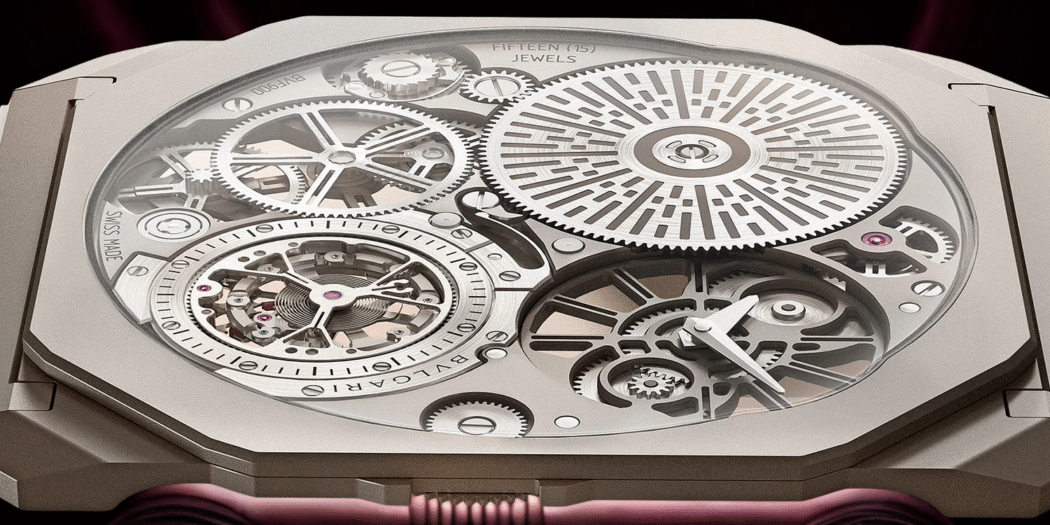

The twenty-first century reignited this mechanical obsession in a new, intensely competitive form. Bulgari, often underestimated as merely a jewellery house, transformed into a powerhouse of haute horlogerie precisely because of its dedication to ultra-thin design. Leveraging the expertise inherited from its acquisitions of Gerald Genta and Daniel Roth, Bulgari embarked on a series of record-breaking attempts. The Octo Finissimo collection, beginning in 2014, became synonymous with engineering audacity. Each iteration set a new benchmark: thinnest tourbillon, thinnest automatic, thinnest minute repeater. And in 2022, Bulgari unveiled the Octo Finissimo Ultra, a staggering 1.80 millimetres thick in total. To appreciate the scale of this achievement, consider that a standard two-pence coin measures roughly 1.85 millimetres. The entire watch, case and movement combined is thinner than that coin.

The technological wizardry behind the Ultra was extraordinary. The movement, calibre BVL180, was integrated directly into the case, so the back of the watch became the baseplate itself. Traditional screws were eliminated in favour of bonding and micro-welds. Bridges and wheels were redesigned to exist almost as negative space, while the hour hand sat flush within a cut-out on the dial. The crown was removed entirely, replaced with horizontal selectors and micro-wheels to set time and wind the movement. Concepto, the Swiss movement specialist, collaborated on this project, bringing patents for integrated case-movement architecture and ultra-thin component placement. The sapphire crystal, treated to withstand bending and pressure, became an active participant in the watch’s structural integrity rather than merely a protective surface.

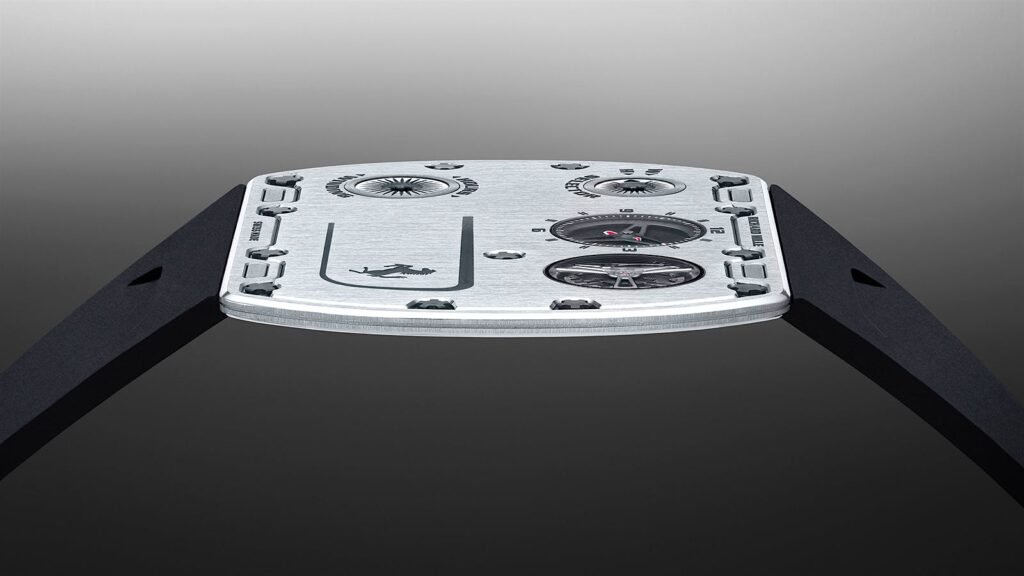

While Bulgari captured the headlines, Richard Mille approached thinness from a different angle, blending industrial architecture with automotive-inspired engineering. The RM UP-01 Ferrari, introduced later in 2022, measured 1.75 millimetres, slightly thinner than the Bulgari Ultra, including crystal and titanium case plates. The movement layout was radical: gears and bridges were rearranged horizontally, balance and barrel existed on a flattened plane, and hands were laser-etched to reduce height. The sapphire crystal, ultra-thin yet resilient, was engineered molecule by molecule. Mille collaborated with Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi (APR&P) to develop two key patents during production: one for horizontal bridge anchoring without vertical stacking, and another for a shock-resistant escapement suitable for the flattened architecture. The tolerances were extraordinary — within 0.05 millimetres — and assembly required specialised microscopes and precision tools unavailable to conventional watchmakers.

Ultra-thin mechanical watches occupy a paradoxical space: they are simultaneously the most delicate and most audacious expressions of horology. They are fragile, expensive, and rarely intended for daily wear, yet they are intensely desirable. The watches are more than timekeepers; they are mechanical statements, almost conceptual art. Collectors prize them not only for their records but for the narrative of innovation they carry. Every component tells a story of machining ingenuity, structural compromise, and human ambition pushed to the edge of what materials allow. Bulgari and Mille are the poster children of this extreme pursuit, but the lineage includes Piaget, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, and many independent watchmakers who have quietly explored ultra-thin design without chasing global records.

Even as records have been set and broken, the physical limits are becoming clear. Sapphire crystals cannot be reduced indefinitely without shattering. Balance wheels require height to clear gear trains. Lubricants behave differently at micrometre scales, threatening reliability. Moving forward, further reductions may depend on materials not yet invented — graphene, silicon alloys, or other composites that retain rigidity while resisting stress. There is also the possibility of hybrid mechanical-electronic watches, where some functions are shifted to microelectronics to allow mechanical components to be reduced even further.

In essence, the modern obsession with thinness is a conversation across decades. From Piaget’s mid-century 9P to Bulgari’s Finissimo Ultra, from Richard Mille’s RM UP-01 to the micro-thin Jaeger-LeCoultre 849, the pursuit of thinness embodies both continuity and innovation. It is about history and heritage, yes, but also about pushing boundaries, discovering what materials and designs can endure, and demonstrating that horology isn’t merely functional but profoundly intellectual. Each new ultra-thin watch is a milestone, a monument to human patience, curiosity, and courage. It reminds us that reduction isn’t simplicity, but a deeply considered, meticulous reimagining of what a watch can be.

While the likes of Bulgari and Richard Mille dominate headlines for record-breaking thinness, the story of ultra-thin horology is also defined by independent watchmakers and smaller ateliers who pursue innovation with equal — if quieter — intensity. Konstantin Chaykin, whom I’ve explored before, is a prime example. His work often defies convention, blending playful creativity with mechanical audacity. Though not always focused purely on extreme thinness, his approach to movement architecture demonstrates the type of lateral thinking required when space is at a premium: every millimetre matters, every wheel and bridge is reconsidered for optimal efficiency and compactness.

Alexey Kutkovoy, another talent emerging from Chaykin’s atelier, has flirted with ultra-thin concepts that could have pushed boundaries even further than mainstream brands. His designs, often experimental, demonstrate a willingness to break traditional rules: using integrated plates, micro-adjusted escapements, and horizontal wheel layouts that minimise vertical stacking. While many of these prototypes never reach commercial production, they act as laboratories for the ideas that trickle into more widely available watches, influencing designs at both Bulgari and Richard Mille.

Meanwhile, François-Paul Journe, though not directly competing for extreme thinness in the same public way as Bulgari or Mille, embodies a parallel philosophy: optimisation and mechanical purity. Journe’s movements, particularly in his Chronomètre Souverain and Tourbillon Souverain, often explore the reduction of mass and height in gear trains, bridges, and escapements. He approaches thinness not merely as a record but as an extension of elegance and horological philosophy, reminding collectors that mechanical sophistication and thinness need not be mutually exclusive.

Even outside Europe, Japanese ateliers such as Credor and Citizen have explored ultra-thin mechanical and hybrid movements. Credor’s Spring Drive line integrates a glide-wheel and micro-gear train in astonishingly thin plates, often under 3 millimetres, with the goal of maintaining torque and chronometric stability in a restricted space. These innovations may not always appear in glossy record-breaking announcements, but they reinforce a crucial idea: ultra-thin watchmaking is as much about cumulative learning as it is about headline-grabbing feats. Every component, every assembly technique, and every surface treatment becomes an exercise in miniaturisation.

Patents underscore the depth of technical achievement in this realm. Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo Ultra is protected by multiple filings covering the integrated case-movement architecture, bonded bridges, and micro-welded components. Richard Mille’s RM UP-01 Ferrari secured patents for horizontal bridge anchoring and shock-resistant escapements, while also applying proprietary coatings to reduce friction between wheels at micron-scale tolerances. Piaget’s 1960s micro-rotor patents remain foundational, influencing designs for decades and guiding the geometry of contemporary ultra-thin automatic movements. Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin have maintained a steady stream of patents addressing thin bridges, torque distribution, and escapement stabilisation, demonstrating that progress is cumulative, iterative, and often fiercely guarded.

Materials science plays a critical role in this pursuit. Sapphire crystals, ultra-thin yet resilient, act as structural components. Titanium and high-grade alloys offer rigidity without excess bulk. Diamond-like coatings reduce friction, while advanced lubricants function at scales where even surface tension can impede performance. Each of these innovations represents an intersection of engineering, chemistry, and horology. Without them, watches thinner than 2 millimetres simply would not function reliably.

The obsession with thinness also extends to ergonomics and wearability, though paradoxically, extreme thinness sometimes sacrifices these qualities. Bulgari’s Ultra and Mille’s RM UP-01, for instance, are more concept watches than daily wearables. Hands are micro-etched or recessed, crowns are removed, and winding often requires dedicated tools. The user experience is secondary to engineering triumph. Yet even in this context, collectors find immense appeal: these watches are tangible representations of human ingenuity pushed to its extreme. They are monuments to ambition and precision, more about the story of creation than the act of telling time.

Historically, thinness has always been both a challenge and a prestige marker. Vacheron’s early pocket watches, Piaget’s 9P and 12P calibres, and Jaeger-LeCoultre’s ultra-thin movements communicated technical mastery to patrons who valued discretion, subtlety, and refinement. Today, Bulgari, Mille, and select independents carry that tradition forward in a more visible, competitive arena. The lineage is unbroken: each generation builds upon the knowledge and discoveries of the last, refining tolerances, discovering new alloys, and exploring novel assembly techniques.

In many ways, this pursuit parallels other extreme engineering fields. Think aerospace, Formula 1, or microprocessor fabrication. Every micron matters, and failure can be catastrophic. Yet in watchmaking, the challenge is compounded by the desire to maintain aesthetic appeal and the tactile poetry of gears and levers in motion. It’s not merely reduction for reduction’s sake; it’s reduction as philosophy, as proof that human ingenuity can bend materials and design to a nearly unimaginable degree.

As the frontier narrows, we are approaching physical limits. Crystals can only be so thin before they fracture. Hands require minimal height to avoid collision with the wheel train. Oils and lubricants must perform reliably in a fraction of a millimetre of clearance. Future reductions may require materials and technologies that do not yet exist — hybrid mechanical-electronic systems, advanced composites, or metamaterials that combine lightness with extraordinary rigidity. Even so, the obsession persists, fuelled by curiosity, ambition, and the desire to leave an indelible mark on horological history.

By now, it is clear that ultra-thin watches occupy a unique niche in horology: they are simultaneously feats of engineering, works of art, and symbols of prestige. The fascination with thinness goes beyond technical achievement; it taps into a deeper human impulse to push boundaries, to explore the extreme edges of possibility. Collectors are drawn to these pieces not only for their record-breaking credentials but for the narrative they embody. To own a Bulgari Octo Finissimo Ultra or a Richard Mille RM UP-01 Ferrari is to possess a story of relentless innovation, a story in which patience, obsession, and precision converge into a tangible object that defies expectation.

Exclusivity amplifies the allure. These watches are rarely produced — often fewer than a dozen units for the most extreme models. Bulgari’s Ultra, limited to ten pieces, each engraved with a QR code linking to an NFT artwork, transforms ownership into both a technical and cultural experience. Richard Mille’s RM UP-01, with its $1.8 million price tag and limited run, functions as a statement of status and taste, signalling that the owner appreciates not just timekeeping but the intellectual audacity required to craft such a watch. In this way, ultra-thin watches occupy a dual space: part technical marvel, part cultural artefact.

The psychology of collecting these timepieces is fascinating. There is an almost ritualistic appreciation of precision, of human ingenuity compressed into a wafer-thin case. Collectors often describe the experience of handling these watches as meditative; the micro-engineering evokes awe, but also humility. Every wheel, every pivot, every micro-bridge is a testament to skill, patience, and the willingness to challenge conventions. The watches themselves are quiet teachers: they reward knowledge, curiosity, and attention to detail, revealing their secrets slowly, encouraging deep engagement rather than superficial admiration.

This philosophical dimension has historical roots. Consider the mid-century Piaget 9P or 12P calibres. While thinness was originally a marker of elegance, it also represented discipline and intentionality in design: a reduction of excess, a stripping away of what was unnecessary. Modern ultra-thin watches echo this principle, but on a far more extreme scale. In a world obsessed with size, with loudness and ostentation, the pursuit of thinness is a quiet rebellion — an insistence that the most impressive feats can be achieved with minimal material, minimal visual presence, yet maximal ingenuity.

Technical obsession, aesthetic restraint, and exclusivity combine to form a cultural phenomenon. The ultra-thin watch becomes a symbol of a collector’s understanding of horological history and appreciation for mechanical artistry. It is a conversation piece, yes, but also a meditation on limits, a demonstration that human creativity can negotiate, and even redefine, the boundaries imposed by physics and materials science. The psychological satisfaction derived from owning, studying, or simply appreciating these watches cannot be measured in hours or minutes; it exists in the recognition of achievement and mastery.

The quest for thinness also underscores a broader narrative within watchmaking: innovation often arises from constraint. By challenging engineers to create the thinnest movement, case, or complication, brands inadvertently develop new methods, materials, and processes that ripple throughout the industry. Bulgari’s bonding techniques and horizontal movement integration have influenced other high-end manufacturers. Richard Mille’s work with APR&P on horizontal bridge anchoring and diamond-like coatings informs wider practices in micro-engineering and component durability. Even Japanese houses such as Credor and Seiko incorporate lessons learned from extreme miniaturisation into consumer models, demonstrating that obsessive engineering in high-end watches benefits the industry as a whole.

Looking forward, the frontier of thinness remains tantalisingly close to physical limits. Crystal thickness, balance wheel clearance, and lubricant behaviour impose constraints that are difficult, if not impossible, to overcome with current materials. Yet horology has always been about pushing the edge of what is feasible. New alloys, graphene composites, hybrid mechanical-electronic systems, and metamaterials may allow further reductions, but the philosophy remains constant: thinness is not merely a number; it is a manifestation of precision, restraint, and ambition.

Ultimately, ultra-thin watches are more than timekeeping instruments. They are milestones of human ingenuity, markers of technological evolution, and artefacts of artistic ambition. They remind us that horology, at its most extreme, is a conversation between past and present, maker and observer, materials and imagination. They demonstrate that obsession — when channelled through skill, patience, and creativity — produces objects of profound beauty, even when measured in microns. From Piaget’s pioneering micro-rotors to Bulgari’s Finissimo Ultra and Richard Mille’s RM UP-01, the pursuit of thinness is a story of audacity, dedication, and the relentless human desire to see how far ingenuity can go.

In the end, the ultra-thin watch stands as a monument to ambition. Each one is a whisper of the past, a statement in the present, and a challenge to the future. They remind us that even in the tiniest, most delicate forms, the spirit of innovation can roar louder than any conventional horological achievement. To admire these watches is to admire the extremes of human curiosity, the courage to challenge norms, and the relentless pursuit of perfection, one micron at a time.

At the extreme edges of thinness, horology transforms into a discipline that resembles both architecture and surgery. Every component, every pivot, every layer of oil or coating matters, and traditional assembly techniques give way to bespoke processes. Consider the assembly of Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo Ultra: with the movement integrated into the case, conventional screwdrivers and bridges become obsolete. Micro-welds and bonding techniques replace screws, while specialised alignment tools ensure that wheels and levers sit perfectly flush. Even a fraction of a millimetre misalignment could prevent the watch from functioning, emphasising the unforgiving nature of working at this scale.

Richard Mille faced similar challenges with the RM UP-01 Ferrari. The horizontal arrangement of wheels and bridges required a completely reimagined assembly sequence. Watchmakers could no longer rely on gravity to aid gear placement, nor could they use traditional jewel bearings in standard positions. Instead, each component had to be micro-fitted under a microscope, with tolerances measured in microns. The sapphire crystal itself became a structural element, demanding that its integration be flawless — any unevenness could bend or distort the movement. Techniques originally developed in aerospace and high-precision electronics were repurposed for horology, demonstrating that ultra-thin watches sit at the intersection of multiple engineering disciplines.

Lubrication at these scales presents another frontier. Traditional oils behave differently in micrometre-thick gaps. Surface tension and capillary effects become critical, threatening efficiency and reliability. Brands have experimented with diamond-like coatings, specialized synthetic oils, and micro-grooving on wheel teeth to maintain energy transmission. Bulgari, for example, applied proprietary coatings to reduce friction on the BVL180’s ultra-thin wheels, while Richard Mille adjusted escapement geometries to function reliably under drastically reduced oil volumes. These innovations underscore that achieving thinness is not merely about removing material but about reengineering the fundamental physics of the movement.

Tooling and instrumentation also evolve in tandem. Ultra-thin assembly demands microscopes with higher magnification, tweezers with sub-millimetre tips, and torque-controlled micro-drivers. Even measuring devices must be adapted: micrometre calipers and laser-based systems replace conventional gauges to ensure that tolerances are within design specifications. Training watchmakers for these tasks becomes a specialized art in itself. Not every atelier is equipped to attempt extreme thinness, and not every watchmaker has the patience, skill, or vision to succeed. It is, in many ways, a discipline unto itself.

Looking to the future, the pursuit of thinness will likely intersect with new materials and hybrid approaches. Graphene, carbon composites, and silicon alloys offer extraordinary rigidity at minimal thicknesses, potentially allowing for sub-millimetre movement architectures that retain strength and reliability. Hybrid mechanical-electronic systems could permit some functions to be offloaded to micro-circuits, freeing space for gears, barrels, and escapements to be reduced further. Yet each technological advance will require new design philosophies, fresh patents, and intensive testing, ensuring that the pursuit of thinness remains as much about creativity and problem-solving as it is about numbers.

Culturally, ultra-thin watches will continue to serve as statements of intellectual curiosity and mechanical prowess. Collectors are not simply buying a timepiece; they are engaging with a story of human ambition, engineering courage, and historical lineage. Each record-breaking watch serves as a touchstone, connecting Piaget’s mid-century micro-rotors with Bulgari’s Finissimo Ultra, Richard Mille’s RM UP-01, and the experimental work of independents such as Chaykin and Kutkovoy. The lineage is visible, traceable, and audibly resonant: every movement hums with the accumulated knowledge of decades of horological exploration.

In conclusion, the quest for ultra-thin watches is far more than a game of millimetres. It is an exploration of physical limits, an exercise in micro-engineering, and a demonstration of how human creativity can impose order and function on extraordinarily constrained spaces. From early twentieth-century dress watches to modern record-breaking marvels, the obsession with thinness represents the convergence of precision, ambition, and artistry. The watches themselves are ephemeral in comparison to the ideas they embody; they are less about telling time and more about challenging what is possible. In an era where mass production dominates, these pieces stand as reminders that horology remains an arena for experimentation, mastery, and daring.

Every ultra-thin watch carries a message: that the boundaries of design and engineering are not fixed, that obsession can yield beauty, and that even the smallest, most delicate forms can host the greatest achievements of human ingenuity. Whether through Bulgari’s structural innovations, Richard Mille’s aerospace-inspired assembly, or the subtle experimental work of independent artisans, the pursuit of thinness continues to inspire, provoke, and redefine the limits of watchmaking. The story is far from over, and with each micron shaved, a new chapter is written — a testament to the enduring allure of precision, audacity, and the pure, relentless art of horology. My personal opinion is that it’s likely to be the Konstantin Chaykin’s of the world who started out with humour in their creation, but it’s no joke that this man has the ability to challenge anyone when it comes to the world’s thinnest watch.

Just About Watches

Just About Watches