If you think back to your first significant watch, you’ll probably remember less about the technical specifications than about the moment it entered your life. The dial colour, the lume, the clasp—all of those details matter, of course, but what burns into memory is the context. Perhaps it was a gift for a birthday or a graduation, perhaps you saved for months to buy it yourself, perhaps it was a spontaneous purchase after something life-changing, whether joyous or devastating. That moment of acquisition is where the watch fuses with memory, and psychology tells us it’s not an accident. The human brain is built to anchor emotion in objects. The hippocampus and amygdala—key centres for memory and emotional processing—are activated in tandem when we mark milestones, which is why we reach for something physical to commemorate intangible feelings. A watch becomes more than an accessory at that instant; it becomes a symbol, a neurological placeholder for the experience we don’t want to fade.

There’s a biological basis for our joy when buying or receiving a watch. The brain’s reward system is governed by a cocktail of neurotransmitters—dopamine, serotonin, endorphins, oxytocin—that fire when we achieve something. It doesn’t have to be grand. A promotion, a marathon, a degree, surviving a rough patch—any milestone that feels hard-earned leaves us seeking closure. And closure, psychologically, is often represented by a token. This is known in behavioural sciences as symbolic reinforcement. The object becomes the stand-in for the emotion. It’s not about steel or sapphire crystal or automatic versus quartz—it’s about creating an externalised anchor for an internal state. Every time we wear it, the brain reactivates those neural pathways. It’s not indulgent—it’s memory encoding. That’s why a watch isn’t just a luxury purchase; it’s a neurological souvenir of an achievement, and sometimes, of survival.

“Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome.”

-Booker T. Washington

In our Facebook group Just About Watches, I recall a member who shared the story of buying a Tudor Black Bay Fifty-Eight after completing chemotherapy. To him, it wasn’t a luxury indulgence; it was survival embodied. He said, “I didn’t want to forget what I came through. That watch is a reminder of what I can handle.” It didn’t matter that it was a Tudor and not something more exotic. What mattered was that it carried a chapter of his life in its bezel and bracelet. In a very real sense, it wasn’t consumerism. It was architecture. Emotional architecture. He was building resilience into a physical object he could wear daily, a reminder that strength is not just a story we tell ourselves—it can be held, felt, clasped around the wrist. This is the side of watch ownership outsiders don’t see. From the outside, it might look like overpaying for steel and gears. From the inside, it’s something closer to survival therapy, coded into metal.

Psychologists Lyubomirsky, King, and Diener found in 2005 that success and happiness create a feedback loop. Achievement produces joy, and joy fuels further achievement. When you mark those achievements with something tangible, like a watch, you embed that loop into your life. Every glance at the dial is a reminder not just of the time, but of the strength that brought you there. The habit of rewarding oneself is often misunderstood as vanity or indulgence, when in reality it is one of the most powerful self-motivational strategies we have. In fact, it goes beyond motivation—it becomes a mechanism of identity reinforcement. When you gift yourself a watch after overcoming something monumental, you’re not saying, “Look at me.” You’re saying, “Remember me.” Remember what I endured. Remember who I was. Remember what I can be again.

Emotional design, as discussed by Don Norman and others, argues that good design isn’t just functional — it makes us feel something. A colourful watch may be ‘silly’, but its psychological function is often profound. It unlocks parts of ourselves we’re taught to tuck away.

The truth is, even the smallest moments get stored this way. Someone buys a Seiko after their first paycheque and wears it until the strap falls apart. Someone else buys a vintage Omega because it was the watch their grandfather wore, and even though it’s not the same one, it feels like a reunion with the past. In both cases, the watch becomes a bridge. A neurological shortcut to an emotional truth. Without it, those moments are vaguer, more prone to fading. With it, they’re locked in. That is the true reward system at play in watch collecting—it isn’t just about new watches, but about new meanings carried forward.

As such, when we talk about watches as investments, we often miss the greater truth. Yes, values rise and fall. Yes, some people flip watches for profit. But the deeper return is psychological, not financial. A Rolex Daytona might double in market price over a decade, but for the owner who bought it after their child was born, the true appreciation is emotional. It grows in meaning every year, not in currency. Even a watch that loses financial value rarely loses emotional value—unless it was bought without meaning in the first place. That distinction, between the transactional and the transcendental, defines the psychology of collecting far more than any price chart.

There is something almost primal about the way we reward ourselves with an object that tells time, as though centuries of human struggle and adaptation have hardwired us to seek permanence in something tangible when the world around us is in constant flux. A watch is rarely purchased because the owner lacks the ability to track the hours before; the modern phone has already eliminated that need. Instead, the act of acquiring a watch, whether it be a modest Seiko or a grail-level Patek Philippe, is bound up with the language of reward, of recognition, of saying to oneself: I endured, I achieved, I made it through. It is a deeply human pattern, one that traces itself back to the earliest forms of symbolic exchange, when tribes marked survival after winter with talismans, or when hunters returned bearing carved bones as proof of triumph. The modern equivalent is quieter, less bloody perhaps, but no less meaningful—an office worker surviving a punishing year of deadlines and politics might choose to mark the ordeal with a gleaming piece of steel on their wrist, a personal flag planted on the mountain of self-worth.

Psychologists studying reinforcement theory have long noted that the most powerful rewards are not the functional or utilitarian ones but those bound up with narrative. A bonus cheque deposited into the bank soon blends into the fog of household expenses, yet a watch bought with that same bonus crystallises the story of perseverance into something lasting. In cognitive behavioural terms, it becomes an anchor, a physical object that is forever associated with the emotion that birthed it. This is why the thrill of unboxing a new watch can feel almost disproportionate to the object itself—the polished bezel, the sweep of the second hand, the crisp clasp snapping shut all communicate not just the presence of a new tool but the embodiment of a chapter in one’s life. Each time the owner glances at it, the dopamine pathways re-ignite, recalling not only the satisfaction of purchase but the journey that led to the moment, whether it was a promotion, a recovery, or the quiet celebration of simply surviving another year.

But what makes this reinforcement unique is that it transcends the individual moment and often grows in significance over time. A birthday gift might at first seem like a token, but years later, when the giver is gone or circumstances have shifted, the object morphs into something far weightier. A battered Timex handed down from father to son ceases to be a measure of punctuality and becomes instead a portable shrine, a reminder of presence and continuity. Neuropsychologists call this “emotional tagging,” where a neutral object absorbs the affective charge of the context it is tied to, embedding itself within the hippocampus as a retrieval cue. The reason someone may find themselves stroking the bezel of a parent’s old watch during moments of stress is not sentimentality alone but a neurological feedback loop: the watch has become fused with the reassurance and identity of the loved one, a totem that collapses time and grief into something both bearable and tactile.

This relationship between reward and memory explains why watches so often accompany life’s milestones. Graduation watches, wedding-day watches, retirement watches—the rhythm of life is punctuated by these metallic markers as if the calendar itself is incomplete without a wristwatch to embody the transition. Yet the deeper truth is that the watch is not marking the moment; the moment is marking the watch. Each scratch on the clasp, each worn patch on the strap becomes a palimpsest of lived experience. When collectors romanticise “patina,” they are not only praising the aesthetic of aged lume or weathered dials but unconsciously responding to the narrative density encoded within the imperfections. To own a watch that has been through storms, sweat, and decades is to wear a compressed biography on the wrist. It is why even in an age of pristine reissues and careful curation, a beat-up old Rolex Submariner with faded bezel still commands a visceral allure: it represents time lived, not just time told.

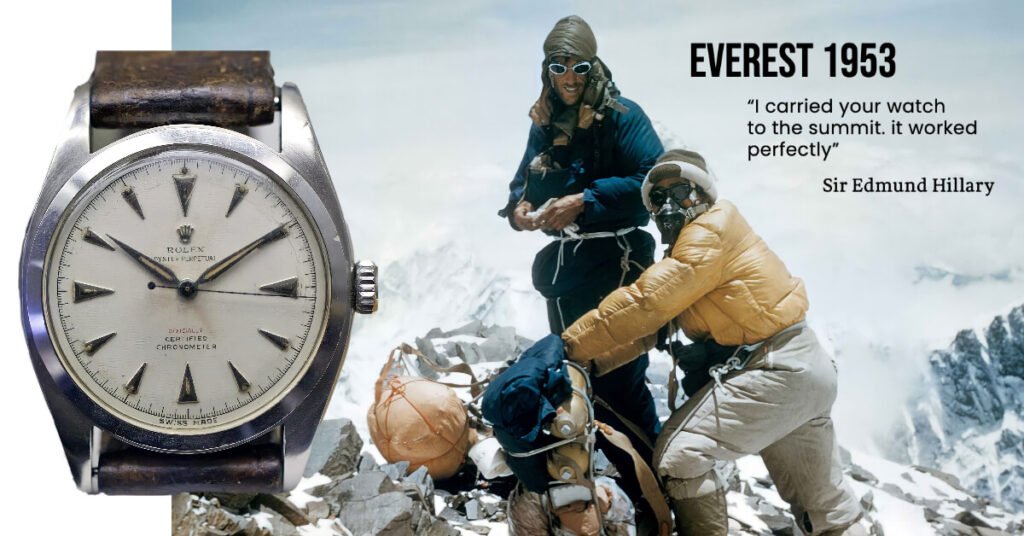

Of course, this psychology of reward has not gone unnoticed by brands, who weave it directly into their marketing strategies. They no longer sell timekeeping devices—they sell stories of achievement waiting to be claimed. Rolex advertisements rarely discuss accuracy or technical details; instead, they show a summit, a yacht, a tennis court, and by implication suggest that to wear the watch is to have arrived at a pinnacle worthy of self-congratulation. The brilliance of this approach lies in its ability to leverage the consumer’s innate desire for symbolic reinforcement while disguising it as mere aspiration. The buyer does not see themselves as succumbing to advertising but as affirming their own journey. It is a clever psychological sleight of hand, one that blurs the line between intrinsic reward and extrinsic suggestion, leaving the wearer convinced that the watch is their choice, their trophy, their proof—when in truth the seed of desire was carefully planted.

But to dismiss it all as marketing manipulation would be to underestimate the agency of the wearer. Many people resist the top-heavy narratives of luxury brands and instead forge their own rewards with less heralded watches. A young nurse who buys a humble Casio after their first year of gruelling night shifts is engaging in the same symbolic ritual as a CEO unboxing a platinum Day-Date—both are claiming survival, both are recognising growth. In some ways, the nurse’s choice is even more authentic, precisely because it is not contaminated by the weight of status projection. The reward is private, personal, almost defiant. This is where the beauty of the psychology lies: the object need not be expensive to be meaningful, for its value comes not from the metal or the logo but from the story grafted onto it by human experience.

The reinforcement is also cyclical. A watch that once marked one milestone often becomes the motivator for the next. Someone might glance at their wrist before a difficult meeting and recall the battles already endured to obtain that piece, drawing courage from its silent testimony. The object becomes a feedback system: you reward yourself with it, then it continues to reward you by reminding you of your resilience. This is what makes watches unusual compared to other consumer goods. A new phone, however exciting at the time of purchase, rarely carries long-term symbolic weight; it becomes obsolete, replaced, and forgotten. A watch, by contrast, can resist obsolescence precisely because its core function is not utility but identity. In a world where almost everything ages into redundancy, a watch can paradoxically gather strength with years, becoming more powerful as a psychological token the older and more worn it becomes.

The reinforcement is also cyclical. A watch that once marked one milestone often becomes the motivator for the next. Someone might glance at their wrist before a difficult meeting and recall the battles already endured to obtain that piece, drawing courage from its silent testimony. The object becomes a feedback system: you reward yourself with it, then it continues to reward you by reminding you of your resilience. This is what makes watches unusual compared to other consumer goods. A new phone, however exciting at the time of purchase, rarely carries long-term symbolic weight; it becomes obsolete, replaced, and forgotten. A watch, by contrast, can resist obsolescence precisely because its core function is not utility but identity. In a world where almost everything ages into redundancy, a watch can paradoxically gather strength with years, becoming more powerful as a psychological token the older and more worn it becomes.

In extreme cases, this reinforcement can even shape behaviour beyond the act of wearing. Collectors often describe a sense of “earning” the right to buy their next watch, creating arbitrary goals to justify acquisition. Run that marathon, finish that project, overcome that personal hardship—then, and only then, will the new chronograph or diver join the collection. This self-imposed gamification might look irrational from the outside, but from within it makes profound sense. It externalises motivation, giving tangible stakes to otherwise abstract struggles. The watch becomes both the carrot and the certificate of completion, a hybrid object that pulls one forward and simultaneously seals the victory. In this way, horology does not merely reflect life milestones but actively structures them, acting as an invisible architecture of motivation and memory.

And yet, there is also a shadow side to this pattern, where the reward dynamic can slip into compulsion. Just as the gambler keeps pulling the lever in search of another hit of dopamine, some collectors find themselves trapped in an endless loop of acquisition, chasing not the watches themselves but the fleeting psychological high of reward. The once-meaningful ritual of self-congratulation becomes hollow, the watches pile up, and the original stories that gave them meaning blur into a haze of cardboard boxes and shipping receipts. In this sense, the very mechanism that makes watches such profound tokens of human experience can also ensnare those who forget the narrative and focus solely on the next purchase. It is here that the delicate balance between symbolic reinforcement and consumer compulsion must be reckoned with, for the watch is not immune to the darker urges of the human psyche.

If reward and reinforcement give the watch its psychological gravity, then emotional design is what makes the object sing in the first place. Strip away the symbolic stories for a moment, and you are left with a small machine, a circle of metal strapped to a wrist. By rational terms, it is almost absurd that such an object could stir the kinds of feelings it does. And yet, those feelings are not accidents—they are the result of carefully orchestrated design choices, both conscious and unconscious, that reach deep into the human sensorium. A case brushed in satin steel communicates toughness and modernity, while one polished to a mirror finish evokes elegance, fragility, and even a touch of vanity. The heft of a gold case against the wrist is not simply a matter of grams but an embodied reminder of permanence and indulgence. In every curve, colour, and material lies a psychological trigger, a quiet invitation to feel something more than the passage of time.

Industrial design theorists have long argued that objects have three dimensions of emotional impact: visceral, behavioural, and reflective. Watches exemplify this trifecta better than almost any consumer good. The visceral is immediate—the sparkle of a sunburst dial catching morning light, the luminous green of a diver’s indices glowing faintly in a dim room. These are instant, sensory impressions that bypass rational thought. Then comes the behavioural, the subtle pleasure of winding a crown, of hearing the satisfying click as a bezel rotates precisely into place, of feeling a clasp lock with reassuring certainty. Finally, there is the reflective, the higher-level meaning we assign after repeated encounters, the sense that a Bauhaus-inspired dial represents clarity of thought, or that a skeletonised tourbillon reflects openness and complexity in one’s worldview. Together, these dimensions weave a web of engagement that makes the watch not just an accessory but an experience layered into everyday life.

Colour alone has an astonishing influence on how a watch is perceived and loved. A deep blue dial may conjure the serenity of oceans, tapping into evolutionary associations with water as life-giving. Green dials, once niche, have surged in popularity not merely by chance but because of their biophilic resonance—green is the colour of growth, renewal, and stability. Red accents can energise, suggesting danger or passion, while monochrome schemes play to restraint and timelessness. When collectors argue endlessly over the precise shade of a vintage “tropical” dial, they are not being pedantic so much as responding to the subconscious pull of colour psychology. What makes a faded brown dial more alluring than a perfectly preserved black one is not objective superiority but the way that brown communicates warmth, earthiness, and the passage of time. A tiny shift in hue can alter an entire narrative, transforming cold functionality into romantic nostalgia.

Material choice magnifies these effects even further. Stainless steel, once considered utilitarian and even inferior to gold, has over the decades become the darling of modern collectors precisely because of its emotional ambiguity. It is democratic, functional, robust, yet capable of astonishing refinement in the hands of a skilled polisher. Gold, in contrast, shouts where steel whispers, enveloping the wearer in a glow of opulence that cannot help but evoke ritual and ceremony. Titanium carries connotations of aerospace, technology, and lightness against strength, appealing to a mindset attuned to innovation and performance. Ceramic, with its smooth, almost skin-like touch, removes warmth but adds an otherworldly permanence, resistant to scratches yet vulnerable to shattering. Each material is not just a technical choice but a psychological one, encoding layers of cultural meaning that seep into how a watch makes its owner feel each day.

And then there is tactility, a sense that cannot be faked in renderings or catalogue shots. The first time one depresses a chronograph pusher and feels either a crisp click or a mushy give, the hand sends signals to the brain that shape judgment instantly. Collectors may spend hours debating movements and calibres, but the real love affair often begins with these micro-interactions: the winding of a buttery smooth crown, the resistance of a bezel that aligns with mechanical perfection, the way a leather strap warms and moulds to the wrist with time. Neuroscience reminds us that touch is one of the most ancient senses, deeply tied to emotional processing. To touch an object daily, to feel it literally pulse with life if mechanical, is to establish an intimacy that words barely capture. Watches are not just worn—they are caressed, handled, bonded with, in ways that elevate them above mere tools.

Shape and proportion also play profound psychological roles, often unconsciously. The preference for round cases is not purely traditional but may stem from deep-seated cognitive ease: circles are associated with harmony, continuity, and even safety. Square or rectangular watches evoke precision and authority, lending themselves to dressier, more assertive personas. Thickness, too, alters identity—a slim ultra-thin whispers of discretion and refinement, while a chunky diver radiates readiness and ruggedness. Lug shape can make the difference between aggression and elegance, while dial symmetry or asymmetry tugs at our innate biases toward order or dynamism. Designers know this instinctively, which is why even subtle adjustments can completely shift how a watch is received. A millimetre shaved from a bezel, a date window moved fractionally closer to the centre, and suddenly the emotional resonance changes, like altering a note in a familiar melody.

These aesthetic and tactile elements converge most dramatically in the ritual of trying on a watch for the first time. The lighting, the feel of the strap being tightened, the tilt of the wrist to see the dial—it is a small theatre of emotions, heightened by the sensory richness of design. The buyer is not evaluating specifications but imagining themselves within the emotional universe the watch projects. A rugged chronograph might conjure mountain expeditions, even if the wearer never ventures further than the office; a delicate enamel dial may whisper of candlelit dinners and old-world grace. The watch is a canvas onto which fantasies are projected, and the design is the palette that makes those fantasies believable. Without this emotional design language, no amount of marketing spin could make a lump of gears and screws into something so coveted.

Yet what makes watch design even more powerful is its ability to trigger nostalgia. A reissue model with faithful vintage details can stir feelings in buyers who never lived through the original era, tapping into what psychologists call “vicarious nostalgia.” A faded lume or a plexiglass crystal, carefully reproduced, activates a yearning for a time imagined rather than remembered. This is where the line between authenticity and manipulation blurs, for brands deliberately play to these triggers. But the emotional truth remains valid: the watch becomes a vessel through which the wearer connects with a romanticised past, enriching their present experience. This ability to travel emotionally through time is unique to horology, for watches themselves are timekeepers that simultaneously evoke eras gone by.

The interplay of emotional design also explains why certain watches, technically unremarkable, inspire cult devotion. A Swatch with a quirky pattern, a G-Shock in a limited colourway, a quirky independent microbrand piece—they may lack haute horology credentials, but they ignite joy because their design resonates with personality. In this sense, watches are extensions of self-expression, wearable artworks that bypass rational justification. When someone chooses a bright orange dialled Doxa over a safer, monochrome Submariner, they are declaring something about their taste for adventure, their refusal to blend in. Emotional design gives permission to deviate, to claim individuality, and that is perhaps its most profound psychological service: it allows us to see ourselves not as clock-punching units of time, but as characters in a story we ourselves are writing.

If emotional design is what makes us fall in love with a watch at first sight, then identity is what keeps that bond alive long after the novelty fades. We often think of identity as fixed, a set of stable traits that define who we are, but psychology reminds us it is more fluid, more performed, more negotiated than we care to admit. Every day we step into roles—parent, professional, friend, stranger—and in each of those roles, our self-presentation shifts. Watches slide easily into this theatre of identity, sometimes as costumes, sometimes as anchors, sometimes as quiet scripts for who we want to be. They can be masks, but they can also be mirrors, reflecting the subtler truths we carry beneath the surface. It is in this duality—between presentation and essence—that the psychological weight of horology deepens.

Status watches such as Rolex embody this tension in its most charged form. To wear one is to step into a cultural symbol so overburdened with meanings that it can never be neutral. For some, the Submariner or Datejust is the final punctuation mark at the end of years of hard work, a quiet way of telling themselves they have made it. For others, that same watch triggers unease, a creeping impostor syndrome whispering that they have not truly earned it, that the watch speaks louder than their own confidence. The object does not cause these emotions—it surfaces them, forces the wearer to confront their relationship with status and self-worth. One collector described the day he strapped on his first Rolex as both triumph and doubt: “I loved how it looked, but I also kept wondering if people thought I was pretending.” In that contradiction lies the true psychological drama of status pieces—they are not just symbols to the world but tests to ourselves.

And yet, the opposite choice—a deliberately humble Casio or Seiko—can be just as performative, just as identity-laden. The F-91W, a watch that costs less than a dinner out, has been spotted on the wrists of professors, CEOs, and artists, often worn with a wry smile. Its plastic case is not merely practical; it is a statement of detachment from the rat race of luxury. It declares: I do not need precious metals to validate me. But this, too, is a form of signalling, a way of opting out while still very much communicating values. Social psychologists would call this a “counter-signalling” strategy—by rejecting status, one demonstrates that they already possess it. In this sense, even the humblest watch becomes part of a grammar of self-presentation, an active choice that speaks volumes even in silence.

Where identity becomes most fascinating is in moments of rupture—when the watch becomes a tool for rewriting the self. A man who switches his watch to his right wrist after divorce is not merely changing convenience; he is declaring agency, crafting a symbolic break with old patterns. A woman who moves from quartz fashion watches to a hand-wound Cartier Tank might not articulate it, but she is aligning with values of tradition, timelessness, and even control over the ritual of winding. In each case, the object serves as a pivot, a way of externalising and solidifying inner change. Psychology calls these “transitional objects”—things that help bridge one chapter of life into another. They are not luxuries in those moments; they are scaffolding for identity, small but potent props in the theatre of becoming.

Cultural context only deepens these layers. A Rolex in London might communicate ambition and tradition, but in Tokyo, it can be seen as conformity to established symbols of success, while in Mumbai, it might signify security or family prosperity. In Silicon Valley, the cultural elite often lean toward the opposite—smartwatches, G-Shocks, or minimalist independents—to project utility, innovation, and a studied indifference to old-world luxury. What appears on one wrist as brash appears on another as pragmatic. The watch is always part of a language, but the dictionary shifts depending on where you stand. To understand the psychology of watches is therefore to recognise that they are never interpreted in isolation—they are decoded through cultural frames, through group norms, through the silent but powerful influence of others’ eyes.

At the personal level, psychologists such as E.T. Higgins have emphasised the role of congruence between actual self and presented self in maintaining well-being. When what we wear on the outside harmonises with what we feel on the inside, the result is psychological ease, reduced cognitive dissonance, and greater self-confidence. Watches participate in this congruence more directly than most accessories because of their constant visibility. We glance at them dozens of times a day, and each glance is a moment of feedback: Does this feel right for who I am today? When the answer is yes, the watch becomes almost invisible, a natural extension of the self. When the answer is no, even the most expensive piece can feel like a costume, heavy and ill-fitting. Collectors often confess to selling watches that were “technically perfect” but simply “didn’t feel like me.” That feeling is not trivial—it is the embodied experience of congruence or its lack.

Ego, of course, plays a complicated role in this arena. Watches can certainly inflate it—there is no denying that a gleaming Royal Oak or Nautilus can embolden its wearer with a sense of elevated stature. But just as often, the ego finds balance in the quiet ritual of wearing something subtle, something known only to the initiated. Independent makers such as Voutilainen, Dufour, or Brivet-Naudot serve this psychological need beautifully: to wear one is to align with a philosophy, to join an invisible fellowship that values craftsmanship and individuality over broad recognition. The ego here is not erased but refined—it finds nourishment not in mass validation but in intimate coherence with values. In this sense, ego and humility are not opposites in watch psychology but partners, dancing along the spectrum of how we choose to be seen.

The paradox is that even choices framed as purely personal are still relational. A collector who insists, “I wear this for me alone,” is still inhabiting a cultural world where such a statement has meaning. Even privacy is a social act, a refusal to participate in certain games of signalling. Watches reveal this paradox constantly—they are intensely private objects worn in intensely public ways. They are pressed to the skin, yet displayed to strangers. They are for the self, yet inevitably read by others. This duality is perhaps why they fascinate us so deeply—they are mirrors we hold up not just to ourselves, but to the society around us, whether we like it or not.

When all is said and done, the journey through watches and psychology is not a matter of disassembling gears and pinions under a loupe but rather of holding up a mirror to ourselves. What began as an exploration of reward and reinforcement quickly spilt into questions of identity, heritage, and the silent language of design. A watch is never simply strapped to the wrist—it is absorbed into the story we tell about who we are, or who we hope to become. Even the smallest choice, from a brushed caseback to a patinated dial, carries with it a subtle current of self-recognition and self-expression. What makes this fascinating is not that horology has managed to occupy such a space, but that it has done so in a world where the time itself is freely available, glowing at us from every digital surface. That persistence hints at something deeper, something primal, almost archetypal, about carrying time in this form.

The act of acquisition, of keeping, or even simply gazing at a watch in one’s collection is never neutral. It sparks rewards in the brain, both chemical and emotional, anchoring moments in memory and lending structure to how we measure achievement. It is why so many collectors can remember not just when they bought a watch but what they were going through at the time, who gave it to them, or the chapter of life it became fused with. It is why some pieces are harder to sell than others, why some will never leave the box regardless of monetary value, and why others transform into family heirlooms long before the original owner has let go. Watches can embed themselves into identity in a way that other luxury objects rarely manage—far more personal than cars, far more enduring than fashion, and far more intimate than art on a wall.

As we’ve seen, the design language of watches does not just please the eye, it stirs the mind. Minimalist Bauhaus dials appeal to clarity-seekers, chronographs speak to those who measure and control, divers suggest resilience and readiness, while dress watches hum quietly with restraint and dignity. These aren’t accidents of styling but signals, read consciously and unconsciously alike. To strap on a watch is to align with a certain set of values, or at least to project them, whether for one’s own reassurance or for others to pick up on. This is why the psychology of watches reaches so far beyond utility—it is closer to the psychology of selfhood itself.

But if all of this sounds like the story is complete, it isn’t. We’ve only opened the first doors. There are whole avenues still to explore: how ritual and routine feed into the act of winding or checking a watch, how memory and legacy shape the way we pass them on, how culture and region bend the meanings we attach to them, and even how mortality is quietly acknowledged every time we glance at the dial. There is also the curious tension between mechanical timekeepers and their digital successors—the smartwatches that now measure our heartbeats and our health alongside our hours. Each of these deserves its own patient unpacking, and that is exactly where we will go next.

For now, perhaps the only summary worth holding onto is that watches live less on the wrist than in the psyche. They are not tools in the old sense and not ornaments in the trivial sense, but companions that shape how we understand reward, identity, and the passage of time itself. That is why the fascination endures, why enthusiasts can talk for hours without tiring, and why a single reference or design tweak can provoke such intense feelings. Watches are, in the end, pieces of us.

And this is just the beginning.

Just About Watches

Just About Watches